Every city has one.

-Tagline.

Directed by Ted Demme.

Starring Denis Leary, Ian Hart, Famke Janssen, Noah Emmerich, Billy Crudup, Jason Barry, John Diehl, Colm Meaney, Jeanne Tripplehorn, Greg Dulli, and Martin Sheen.

Written by Mike Armstrong & Denis Leary (uncredited).

Cinematography by Adam Kimmel.

Music by Todd Kasow.

Edited by Jeffrey Wolf.

Produced by Ted Demme, Nicolas Clermont, Elie Samaha, Jim Serpico, and Joel Stillerman.

A Miramax release.

“In a tough Irish-American neighborhood, Bobby is a small-time car thief for the area’s top mobster. But when Bobby’s own gang kills members of his family, he is faced with a tough choice: defend his family honour or obey the rigid neighborhood code of silence.”

With a screenplay by Mike Armstrong (1996’s decent, but overlooked, Denis Leary/Sandra Bullock romance, Two If By Sea), Monument Ave (aka Snitch) was marketed as an “Irish Mean Streets,” but mostly dismissed in its day as another in the endless stream of post-Reservoir Dogs/Pulp Fiction Quentin Tarantino knock-offs. It’s so much better than that.

Monument Ave, in contrast to those other pictures, works not only as a compelling, minor-key gangster film, but also as a finely-drawn character study, morality tale, and like Scorsese’s Bringing Out The Dead (expect a future post on that film in this series) would do a year later, it is a surprisingly thoughtful exploration of grief and guilt.

Denis Leary (Judgement Night; Rescue Me) stars, in his best film role, as Bobby O’Grady, a small time car thief but big fish in the local pond that is his South Boston Irish-Catholic neighbourhood.

The viewer gets the immediate impression that Bobby is basically a good guy, that he’s only a criminal because he never found anything else he was any good at.

He’s not particularly greedy, nor violent (except when he’s finally pushed too far), and mostly spends his days and nights hanging out with his lifelong best pals, Mouse, played by Ian Hart (Backbeat, the new season of Shetland), Red, played by Noah Emmerich (Demme’s Beautiful Girls; Peter Weir’s The Truman Show), Digger (John Diehl, Mo‘ Money; Heat), and Bobby’s cousin Seamus (Jason Barry, McCallum), visiting from Ireland.

Their underworld activities feel more like the harmless pranks of a bunch of overgrown juveniles than actual crimes. There’s nothing malicious about their transgressions.

Like the scene where they run down a quiet street at dawn setting off car every alarm on the block just for a laugh.

Or take, for example, the deceptively tense car “chase” that opens the film.

We see flashes of two men inside their respective vehicles, which are racing down a busy street, in what appears to be a hot pursuit, but is revealed to be two car thieves just having a bit of fun on the job before they turn in the Porsche they just boosted.

And what do they do to celebrate the successful grand theft auto that opens the picture? Bobby, Mouse, and Seamus have a sleepover, watch TV, and discuss the famous women they fantasize about, but will never encounter, like Winona Ryder, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Jessica Lange, while cutting up lines from an 8-ball of cocaine.

Demme and his editor, Wolf, use the clever device, introduced in the “chase,” of inserting photos from the recent and long ago past (with Leary’s son Jack standing in as Young Bobby) to suggest their shared history.

It proves to be a very elegant and economical way of stitching back- story into the main narrative with very little screen time and without relying on clunky dialogue for exposition.

As boys, they played “Cowboys & Indians.” As men they’re playing “Cops & Robbers,” only now the stakes are much higher – even if none of them realizes it until it is far too late.

Bobby’s relatively easy-going existence is complicated by another cousin, Teddy, who is more like a brother than a cousin to him.

Teddy is supposed to be in prison doing a three-year bid. He most certainly should not be down at the local pub telling cock ‘n bull stories about outsmarting the feds to get himself early release.

Teddy is played in a fun and flashy extended cameo by a young Billy Crudup between star-making turns in Barry Levinson’s Sleepers (1996) and Jesus’ Son (1999).

Like De Niro’s Johnny Boy in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, Teddy is a walking live-wire who has run afoul of the local crime boss, Jackie, played by a scenery-chewing Colm Meaney (Far & Away; The Van).

Teddy’s tall tale is that he only gave up some lowlife called Perez, and that he would never ever give up Jackie. When the cops asked about the boss, he told them to go fuck themselves.

Neither the audience, nor anyone at the table, finds Teddy’s story very credible, but it seems to pacify Jackie, who raises a glass and toasts to Teddy’s return.

Crisis seems to be averted. For now. But Teddy is the kind of guy who thinks the rules don’t apply to him, and Bobby knows that Jackie is fast running out of patience, and it’s only going to be a matter of time before there are consequences.

And like Harvey Keitel’s Charlie in Mean Streets, Bobby is forced into the unenviable role of playing peacekeeper between these two volatile men that he can’t control.

But also like Keitel in Mean Streets, Bobby is compromised by a secret (and doomed) love affair: in this case, with Katy, Jackie’s neglected and deeply unhappy wife, played by Famke Janssen (GoldenEye), also in her best role.

One of the pivotal scenes in the film is the sequence which begins with the gang sat around a table at their local, telling stories over pints of beers.

We get the feeling that this night is just like hundreds of other nights these guys have spent getting drunk and shooting the shit together. But this night will soon change the rest of their lives.

Demme creates a mood of great conviviality here before pulling the rug out from under us.

Unbeknownst to anyone else at the table, Jackie has ordered Shang, one of his henchman, to take Teddy out.

In a nice bit of sleight-of-hand directing, Shang is first established as just another one of the guys, listening to the story and laughing along with Bobby and the others, before suddenly pulling a gun and, without a moment’s hesitation, squeezing the trigger.

It is a moment of cold, brutal violence, perhaps most shocking for the casual manner in which it is dispensed.

Neither Bobby, his friends, nor the audience sees this gangland execution coming. And because it is so unexpected (preceding the shooting is a long, funny, anecdote about Mouse taking a nap in the middle of a burglary), this eruption of violence, seemingly out of nowhere, hits us hard. As it should.

The sudden change in tone is masterfully handled by Demme, screenwriter Armstrong, editor Wolf, and the entire ensemble cast, allowing each character time to react in the immediate aftermath.

And though Shang pulled the trigger, there is no doubt about who is ultimately responsible for Teddy’s killing. Fucking Jackie.

The relatively small part of Shang is played effectively by Greg Dulli of 90’s rock band Afghan Whigs, who appeared as himself in Demme’s previous picture, Beautiful Girls.

Dulli also served as vocal stand-in for future Monument Ave castmate Ian Hart’s John Lennon in Ian Softley’s underrated 1994 Stu Suttcliffe/Beatles biopic, Backbeat.

Shang makes a hasty exit, passing the smoking gun to Gavin, played by Brian Goodman (writer/director of the Ethan Hawke/Mark Ruffalo crime drama, What Doesn’t Kill You), another one of be gang, without challenge from Bobby or the others. None of them knows what to do. What options do they have? The underworld has a firm hierarchy. They are foot soldiers and Jackie is the general. They are expected to fall in line. And under no circumstances would any of them even about going to the cops.

To solidify this point, mere moments after the shooting stops, appearing almost out of thin air, as though he were the weary ghost of justice herself, is the tired and angry Det. Hanlon, played with great decency by Martin Sheen.

The righteous fury and Irish wit of the role feels a little like a dry run for Sheen’s Capt. Queenan in Scorsese’s 2006 Best Picture-winning Irish mob drama, The Departed (written by William Monaghan.)

As Hanlon surveys the crime scene, Bobby turn to Seamus, visibly the most shaken among them, and raises a finger of warning to his lips. In this neighborhood, you do not talk to the cops. Even if you’ve just witnessed the murder of your own flesh and blood.

As the neighborhood outsider, Seamus serves as the audience surrogate (another effective device to hide expositional seams), and expresses our own shock and horror at the senseless killing we, too, have just witnessed.

In a humorous exchange, when Hanlon is frustrated in his attempt to solicit any witness testimony, he explains how these things work to Seamus. Despite a bar full bystanders, no one will have seen anything because they were all “in the bathroom” at the time of the shooting.

And sure enough, somehow, they very fortuitously all squeezed in there together just as the fatal shots were fired.

As Teddy’s friends and family gather for his funeral, Bobby’s grief and guilt begin to boil over into seething anger.

If this is his best chance to do something about Seamus’ death, Bobby doesn’t take it.

I cut you off? You’re back working the wire factory quicker than you can wipe your ass. End up just like your dad.

Jackie to Bobby in Monument Ave.

Here the real dramatic engine of the film starts up and the film kicks into a higher gear as Bobby is faced with a moral dilemma: follow the code of the street, which dictates that he fall in line and accept the boss’s decision, or follow a deeper code that calls for him to avenge Teddy’s death, even if it means he will probably be killed himself. After all, Jackie is the king in this neighbourhood, and taking on the king has a way of shortening the life expectations for all those under him who would try. As Jackie tells us, “Twenty men have tried to screw me.” None of them are around to tell their side of the story.

Katy interrupts the building tension between Jackie and Bobby, picking a fight meant to humiliate Jackie and appease Bobby at the same time. But she underestimates Jackie’s restraint in the face of an audience.

Jackie strikes Katy and Bobby finally stands up to his boss. But only for a moment. Jackie quickly reminds Bobby of his place and tells him in no uncertain terms that he is in fact going to do the robbery.

That leads to a crackerjack heist sequence that plays like a David Mamet one act tucked inside the larger drama that is the rest of the film as the planning, execution, and aftermath of the robbery are intercut with tension and wit.

Contrasting the events of the robbery with their planning creates great suspense in the moments when the disparity between expectation and reality is at its apex.

Bobby and Mouse successfully break into the third floor of a parking garage and steal a high-end Ferrari, which they drive out of the parking structure in reverse, one assumes, because it just looks cooler.

But every plan has its flaws.

There are always unknowns.

But Bobby is a cool guy. It’s why everybody wants to hang around with him. Even his pal-turned-nemesis, Jackie. And so, Bobby keeps his cool.

They pull “a Sweeney,” and outmanoeuvre the cops.

And having escaped their narrow brush with the law, they return to their neighborhood without incident.

Only things are not all well. There are lights and sirens and onlookers crowding the street around Digger’s car.

And poor Digger has to break the bad news to Bobby.

Something very bad has happened.

Something awful.

Something is broken that cannot be fixed.

And it crushes Bobby’s soul.

In a beautifully played moment that recalls the feeling of Elia Kazan’s On The Waterfront…

Bobby’s world suddenly closes off to him in a moment of deep moral crisis.

Bobby looks up to see neighborhood windows and drapes pulled shut and lights turning off. In this neighborhood, we don’t talk to the cops.

Bobby isn’t ready to accept his part in this tragedy. Not when there is someone else to blame right in front of him.

He puts that burden squarely on Det. Hanlon’s shoulders. If Hanlon hadn’t picked Seamus up, in broad daylight, in front of witnesses, no less, Bobby’s cousin would undoubtedly still be alive.

But Hanlon aims it right back at Bobby. Putting it as explicitly and emphatically as it can be put, if there is any question remaining as to Bobby’s complicity in his own cousin’s death, Hanlon sets the record straight in a tirade that hits Bobby Bobby hard with both barrels.

Teddy Timmons had it coming. Probably would have ended up back in the joint if he’d have lived, but this kid? This kid just got off the boat! He had his whole life in front of him! Then you got ahold of him, and you taught him the rules. Now this! So, if you’re looking for someone to blame, don’t look at me! Take a good luck in the fucking mirror, brother!

-Det. Hanlon to Bobby in Monument Ave.

It’s not what Bobby wants to hear, even if it’s what he needs to hear. So, his first inclination is to anger. It’s a lot easier than taking self-inventory. And since Jackie isn’t around, Hanlon will have to do.

But everywhere Bobby goes, the message is clear. This is on him. And him alone.

Even Bobby’s own saintly Irish mother thinks he’s a disgrace.

Ultimately, Bobby knows that no one is angrier, or blames him more directly for Seamus’ death, than himself. He is going to have to do something.

And as we learned in Godfather II, when the young Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) assassinates local mob boss, Don Fanucci, at the Feast, neighbourhood gatherings in crime pictures are always propitious times to make a killing.

Following in Vito’s footsteps, Bobby chooses the occasion of the big dance at the AOH to take his vengeance.

Demme establishes the revelry of the event, leaning into the Irish flavor of the evening.

And like the Irish rocker Bono once sang…

“Everybody was having a good time…

“Except you…

“You were talking like it was the end of the world.”

Bobby finds Shang at the bar, exchanges a few words that we cannot hear and follows Shang out of the hall into a back room.

There he finds Jackie doing blow and holding court.

But Bobby hasn’t come to shoot the shit or reminisce about the good old days. Jackie owes him money.

Bobby has come to collect what he is owed.

The mood is tense with dim, cold lighting, deep shadows, and cocaine-fueled anxiety.

Miraculously, Jackie has Shang produce Bobby’s cut from the robbery. Jackie even does the unthinkable. He forgives Bobby’s alleged debt. Bobby is back on easy street.

Maybe Bobby doesn’t have to kill Jackie after all. He may think Jackie ordered Seamus’ death, but does he know it for a fact. Maybe he will just have to live with his guilt and grief. But as he takes his money and turns to leave…

Jackie’s feeling too damn good to keep his mouth shut. He’s flush with cash, and chuffed on cocaine. He has to push Bobby a little more. And so he taunts Bobby, in the guise of a rare moment of gratitude, as he tells Bobby he appreciates how he “handled that Seamus situation.”

It stops Bobby cold. But just long enough to pull the gun stashed inside his jacket.

Jackie has just finally pushed Bobby too far.

But Bobby is not a psychopath and this is not the Irish Taxi Driver, either. So, Bobby spares

But of course, Shang killed Teddy, and probably Seamus. The rules of underworld decorum dictate it: Shang’s gotta go.

And now, as Bobby slips away into the neighbourhood’s shadows at night, he has crossed a point of no return.

Which isn’t to say that his problems are over. Not by a Boston mile.

Det. Hanlon stops Bobby in the street minutes after killing Jackie and Shang.

Bobby’s adrenaline spikes as he realizes he is caught.

A tense moment follows where Bobby’s fate hangs in the balance. His life is now completely in Det. Hanlon’s hands.

Hanlon tells Bobby “how this is gonna go. We’re gonna play it your way.”

Seemingly free from legal consequence or criminal reprisal, Bobby simply returns to the bar where everybody knows his name (it is a Boston bar, after all).

He gets a returning war hero’s welcome home reception from his friends at the bar, despite the fact that he just committed a cold blooded homicide.

The king is dead…

Long live the king!

But always remember…

Heavy is the head…

…that wears the crown.

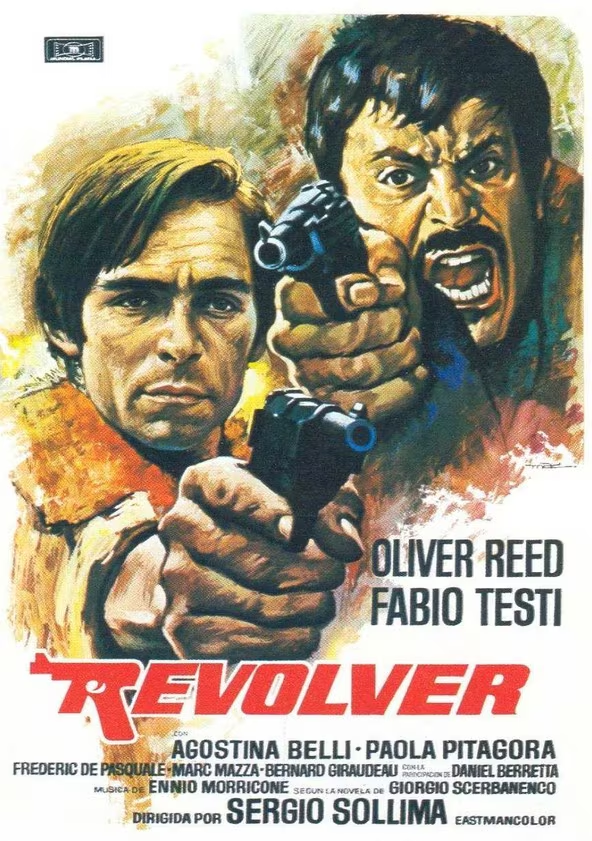

Alternate Posters:

Director Spotlight: Ted Demme

Nephew of legendary filmmaker Jonathan Demme (Silence of The Lambs; Philadelphia), Ted Demme quickly established himself as a talent all his own with the 1993 Yo! MTV Raps buddy cop comedy, Who’s The Man?, starring Ed Lover and Docter Dré (not that Dr. Dre) as the cop buddies, and featuring Leary in one of his first roles as their angry sergeant.

Developing a deep, lasting friendship off-screen, Demme and Leary would continue to work together successfully on multiple projects over the course of their careers.

Ref (1994) original theatrical teaser trailer

Demme’s follow up to Who’s The Man? was Touchstone’s (Disney’s) The Ref, co-written by Oscar-nominee Richard LaGravenese (The Fisher King; Living Out Loud), starring Leary in his breakout role.

Leary plays Gus, a wise-cracking cat burglar forced to play marriage counsellor over Christmas when he breaks into the home of duelling spouses played by Kevin Spacey and Judy Davis.

The film underperformed at the box-office, but was well received by critics. Roger Ebert (officially this site’s favourite) gave the film 3 out of 4 stars and said, “Ted Demme juggles all these people skillfully. Even though we know where the movie is going (the Ref isn’t really such a bad guy after all), it’s fun to get there.”

Demme also directed Leary’s stand-up specials, No Cure For Cancer (1992), and Lock ‘N Load (1997).

Demme’s follow up picture to The Ref was the 1995 romantic-comedy-drama, Beautiful Girls, written by Scott Rosenberg (Things To Do In Denver When You’re Dead).

With shades of Lawrence Kasdan’s The Big Chill, and John Sayles‘ Return of The Secaucus 7, Beautiful Girls is a sweet and funny ode to that particular brand of ennui and nostalgia you encounter in your 20s, when you’re too old to act like a teenager anymore, but too young to feel like a real grown up.

The dramedy boasts a ridiculously stacked cast (Matt Dillon, Mira Sorvino, Uma Thurman, Tim Hutton, Noah Emmerich, Michael Rappaport, Rosie O’Donnell, Lauren Holly, David Arquette, Max Perlich, Martha Plimpton, and Natalie Portman (among others).

Portman’s character’s storyline is the only element which has really aged poorly, that of a 13-year-old girl who would be the object of Tim Hutton’s affection if only she were five years older!

Given the allegations of sexual misconduct levelled against Hutton in the years since the film’s release, and especially those against cinematographer Adam Kimmel (who also shot Monument Ave, Jesus’ Son, and Capote), a registered sex offender charged with child sex assault in 2010, this cringe-inducing subplot, which seemed harmless to me in 1995 (when I was only 2 years older than Portman’s character), now seems so wildly inappropriate I’m hard pressed to imagine how it wasn’t excised from the shooting script, let alone the finished film before release.

Demme did some very good TV work after Beautiful Girls. He directed two episodes of one of the greatest series in the history of television, Homicide: Life on The Street; one episode of the 6-film anthology series Gun, starring a pre-Sopranos-fame James Gandolfini, with other episodes directed by the likes of the great Robert Altman (The Player, Short Cuts), and the very good James Foley (Glengarry Glen Ross, The Corrupter); the Manhattan Miracle segment of the HBO short film anthology, Subway Stories, once again featuring Denis Leary, with contributions from my main man, Abel Ferrara (King of New York, Bad Lieutenant), and Demme’s uncle Jonathan (Melvin & Howard; The Truth About Charlie).

Watch Subway Stories on YouTube for free:

Next came Monument Ave, which Demme followed up a year later with 1999’s criminally slept-on prison-dramedy, Life.

Produced by Brian Grazer (Backdraft; Ransom), Life stars a perfectly-paired Eddie Murphy (Coming to America; 48 Hrs) and Martin Lawrence (Bad Boys 1-4; Blue Streak), doing some of their best work.

Written by Robert Ramsey & Matthew Stone (the Coen Bros.’ Intolerable Cruelty), Life is the surprisingly empathetic story of two wrongfully convicted New Yorkers incarcerated for life in an all black Mississippi prison camp under the oppressive watch of Nick Cassavetes’ (Delta Force 3; Face/Off) white prison guard.

Where the film truly distinguishes itself is in its second-half, when the story begins to speed up to show Murphy and Lawrence advancing into their golden years.

For the excellent artistry and craft that went into the process of creating the progressive looks for each of the characters through the passing years (not even Cassavetes’ prison guard is spared the ravages of time), prosthetics wizard, Rick Baker (An American Werewolf In London) received an Oscar-nomination for Best Make Up.

Even when it feels more gimmick (Norbit) than inspiration (the barber shop scenes in Coming to America; The Nutty Professor), the truth is that nobody manages to be funnier under the weight of heavy prosthetics than Eddie Murphy. Though Lawrence holds his own here, faring much better than in the Big Mama’s House pictures.

Take a look at the scene in Life where Lawrence finally re-encounters society as an old man.

The scene isn’t played for laughs, cheap or otherwise. The make up-prosethics are used in aid of telling the story, not as a gag.

The scene is truly moving in the way it centers Lawrence in a maelstrom of confusing change with gentle compassion.

Lawrence is like The Man Who Fell To Earth here, an alien in a strange world that he doesn’t recognize or understand.

He may be an alien in this place and time, but we are right there in that moment with him, because of the humanity in the writing, directing, editing and, especially, the performing of this scene, which wouldn’t have been out place in Shawlshank.

Life. Was it Jim Morrison who said, “None of us gets out alive”? No truer words.

Though the film was overlooked upon its initial release, a slow re-appraisal has begun to build:

The Best Martin Lawrence Movies and How to Watch Them Online”. CinemaBlend. April 25, 2022.

The Underrated, Classic Buddy Comedy ‘Life’ Turns 21 Today”. The Shadow League. April 16, 2020.

“Beloved Eddie Murphy Comedy Laughs Its Way into Netflix’s Top 10 Charts”. popculture.com. December 5, 2021.

A Forgotten 90s Eddie Murphy Movie is Now Available on Netflix”. Giant Freakin Robot. December 3, 2021.

Butt, Thomas (January 28, 2023). “‘Life’ Shows Eddie Murphy’s Underused Dramatic Chops”. Collider. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

And probably my favourite thing about it is that it refuses to go out on a melancholy note.

Like Michael Keaton and pals in The Dream Team, and Jim Belushi in Taking Care of Business before them, Murphy and Lawrence escape the hooscow to catch a little of America’s favourite pastime.

In the end, though still bickering like an old married couple, Murphy and Lawrence have truly formed a hard won friendship. Watching that develop slowly over a lifetime locked up together is the film’s true joy.

Also of note in Life, among its wonderful supporting cast, which includes Bernie Mac, Ned Beatty, and a silent Bokeem Woodbine (Strapped; The Sopranos) is Nick Cassavetes.

A talented director in his own right (She’s So Lovely; Aloha Dog), Nick is the son of cinema’s premiere iconic power couple, John Cassavetes (Husbands; Killing of a Chinese Bookie) and Gena Rowlands (Woman Under The Influence; Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth).

The young Cassavetes went on to co-write (with David McKenna) Demme’s next picture, 2001’s Johnny Depp (Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands; Jarmusch’s Dead Man) cocaine epic, Blow.

The film co-starred Penelope Cruz (Vanilla Sky; Almodovar’s Volver), Franka Potente (Run Lola Run; The Bourne Identity) RunEthan Supplee (American History X; Wolf of Wall Street); and Paul Reubens (Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure; Batman Returns), in a rare dramatic part.

Adapted from Bruce Porter’s non-fiction book, the film tells the true story of American drug kingpin, George Jung.

Though it grossed $30M over its $53M budget, the film was considered somewhat of a disappointment, drawing unfavourable comparisons to more successful sex, drugs & rock n’ roll saturated dramas of human excesss, like Scorsese’s Goodfellas, and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights.

Ted Demme presents his movie, “Blow,” on Charlie Rose.

Demme’s final film was as co-director with his “The Ref” scribe Richard LaGravenese on the excellent documentary A Decade Under The Influence: The 70’s films that changed everything.

The documentary is a cinephile’s dream, featuring interviews with just about all of the luminaries who made the 1970s the true golden age of cinema. It also serves as the ideal syllabus for anyone unfamiliar with the films of the period wanting to know where to start watching.

Demme tragically passed away before the film was released, suffering a fatal heart attack (supposedly as a result of excessive cocaine use) during a celebrity basketball game on January 14, 2002. He was only 38 years young.

And with that, American cinema lost one of its most promising young directors, but he left behind a legacy of 7 wonderful films, all very different from each other in terms of genre but unified by the great warmth and empathy Demme bestowed upon all of his characters. My kind of filmmaker.

Jonathan Demme dedicated 2002’s Charade remake, The Truth About Charlie to his nephew.

TTAC starred a woefully miscast Mark Wahlberg (Basketball Diaries; Boogie Nights) in the Cary Grant role, and a delightful Thandiwe Newton (the underrated 2Pac/Tim Roth addiction drama Gridlock’d; Jonathan Demme’s Beloved) in the Audrey Hepburn role.

The honour was also bestowed upon the younger Demme by P.T. Anderson, who dedicated his 2002 Adam Sandler vehicle, Punch–Drunk Love, to him.

May he rest in peace.