Starring Clint Eastwood, Jeff Daniels, Wanda De Jesus, Paul Rodriguez, Tina Lifford, Dylan Walsh, and Anjelica Huston.

Written by Brian Helgeland.

Based on the book by Michael Connelly.

Cinematography by Tom Stern.

Music by Lennie Niehaus.

Edited by Joel Cox.

Starring, produced, and directed by Clint Eastwood.

A Malpaso production.

A Warner Bros. release.

Preceded by Space Cowboys (2000).

Followed by Mystic River (2003).

Warner Bros. official synopsis:

“FBI profiler Terry McCaleb almost always gets to the heart of a case. This time, that heart beats inside him. He’s a cardiac patient who received a murder victim’s heart. And the donor’s sister asks him to make good on his second chance by finding the killer. That’s just the first of many twists in a smart, gritty suspense thriller that’s ‘vintage Eastwood: swift, surprising, and very, very exciting!’”

It was an opportunity to do a different slant on detective work, which I’ve been associated with over the years. At this particular stage in my “maturity,” I thought it was maybe time to take on some roles that had different obstacles than they would, say, if I was a man in my 30s or 40s doing these kinds of jobs.

Clint Eastwood on Blood Work.

Eastwood’s underrated 2002 cop-chases-serial-killer picture, Blood Work, was based on the novel by bestselling thriller writer, Michael Connelly, whose work has since been adapted with much greater success on both the big screen: the Matthew McConaughey-vehicle, The Lincoln Lawyer (2011), and small: Netflix’s McConaughey-less The Lincoln Lawyer series; Amazon’s Bosch.

The book was adapted by (sometime) director (A Knight’s Tale; Payback), and prolific screenwriter, Brian Helgeland (Tony Scott’s Man on Fire, 2004), who was on a real career-high in the period between winning an Oscar for his James Ellroy adaptation, LA Confidential (1997), and being nominated for his next Eastwood collaboration, Mystic River (2003), adapted from the book by (sometime) TV-writer (HBO’s The Wire) and novelist (Gone Baby Gone; Shutter Island) Dennis Lehane.

Based upon the opening images, with the camera swooping down from God’s point-of-view, descending on a fresh crime scene just as Clint Eastwood arrives flashing a badge, you could easily be forgiven for coming to this picture cold and assuming within the first few minutes that you’re watching Dirty Harry 6.

Despite superficial distinctions like the fact that Blood Work’s Terry McCaleb is an LA-based FBI-profiler rather than a San Francisco homicide dick, much of the film does play like the natural successor to Eastwood’s last outing as Det. Harry Callahan in 1988’s The Dead Pool.

But there is one significant way in which Blood Work distinguishes itself as not just another entry in the ongoing series of Dirty Harry misadventures: McCaleb is not the indestructible force that Det. Callahan was.

Even as he aged throughout the decades with his off-screen alter-ego, Harry was always, to quote Big Trouble in Little China’s Jack Burton, “kind of invincible.” McCaleb, on the other hand, is vulnerable to the point of fragility.

McCaleb is an older man with a bum ticker, which we learn in the opening sequence when he spots a suspicious man gathered amongst the onlookers at the murder scene. McCaleb gives chase, only for his heart to give out on him before he can collar the suspect, allowing him the opportunity to flee, which he does, though not right away.

In an effectively creepy and surprising moment, which would not have been out of place in something like David Fincher’s genre-best, Se7en (1995), rather than run, the suspect turns, and never letting the light hit his face, comes closer. He seems to be concerned with McCaleb’s well-being as the elderly federal agent collapses against the chain link fence he was unable to scale.

We begin to think the suspect might even help McCaleb, who appears to be fast approaching death’s door – before pulling his piece (not a .44 Magnum, but might as well be) and begins blasting away.

Despite the barrage of bullets McCaleb unleashes in his direction, the suspect manages to escape, though one of the shots wounds him, before it’s lights out for poor Terrry McCaleb.

But McCaleb doesn’t die. He’s given a new heart via life-saving surgery by his frustrated doctor, a small part played well by a ridiculously over-qualified Anjelica Huston.

At this time, Huston’s career was just beginning its late-period flourish. Call it her “Wes Anderson-period,” from The Royal Tennenbaums (2001), through Life Acquatic (2004) to The Darjeeling Limited (2007). Her presence here just adds a touch of class, though one can’t help but wish she had been given more to do.

As for McCaleb, his heart attack has finished his career, but at least he’s still alive. Though he’s not out of the woods just yet. Throughout the picture, McCaleb occasionally raises a hand to his chest, reminding us, and himself, of his precarious mortality. We begin to fear he may not be up to the task. Just about everyone he comes into contact with tells him he looks like death warmed over.

It’s hard to imagine seeing Det. Harry Callaghan in so fragile a state. Dirty Harry doesn’t get heart attacks. He doesn’t even have a heart.

McCaleb seems to have settled into his forced retirement, living an old boat he’s fixing up.

His neighbour in the marina is surfer bum, Buddy Noone, played by Jeff Daniels (The Purple Rose of Cairo; The Newsroom), as a goofy, but harmless and likable harmonica-playing surfer bum.

Buddy alerts McCaleb to the presence of a woman waiting for him on his boat.

Her name is Graciela. She’s read about McCaleb in the paper and wants his help tracking down her sister’s killer.

McCaleb tells her he’s retired and offers to recommend a good private eye. But Graciela believes McCaleb is going to want to help her after all.

“You have my sister’s heart,” she tells him.

The news shakes McCaleb.

It keeps him up at night.

And so he calls Graciela, telling her not to get her hopes up, but promising her he will look into it.

He goes to see the cops working her case, the same two dicks he clashed with at the opening crime scene. He bribes them with some Krispy Kreme donuts for a look at the murder tape.

The more openly hostile of the detectives plays McCaleb the tape, which shows a Good Samaritan entering the store moments after the shooting, trying to save Gloria’s sister’s life. McCaleb thinks the Good Samaritan must have seen the killler, but the tape never reveals his face.

McCaleb visits the scene of the crime and spots the store’s CCTV.

He also picks up a tail.

At the public library he does a little research into the liquor store homicide (and remembers to take his heart pills).

Then visits an old cop friend, who we learn he worked with on the “cemetery man murders,” the case we assume made his career.

The tape shows the killer addressing the surveillance camera directly, though there is no audio. “Yeah, he’s a real chatterbox,” McCaleb’s police friend tells him. MCCaleb remembers the killer appeared to speak in the liquor store tape, too. “Have you given this to any lip readers?” He asks her. She hasn’t. But she sure will.

McCaleb can’t drive with his heart condition so he recruits his marina neighbour, Buddy (Daniels). Buddy worries about McCaleb. “You look tired,” Buddy tells him. “You should get some rest.” It’s good advice.

But McCaleb cannot rest until he catches Graciela’s sister’s killer. He is literally haunted by her murder – dreaming about it from her perspective.

For my money, McCaleb’s nightmare sequence is the best use of negative imagery in any film since Scorsese deployed it in his Cape Fear remake (1991).

With Buddy now in tow as Clint’s personal chauffeur and the audience’s comic relief, McCaleb continues to follow clues, interview witnesses, and search for new suspects.

And as his investigation grows, so too does his relationship with, and affection for, Graciela. Their slow-burn romance is one of the best things about Blood Work. The part of Graciela could have felt like little more than a plot device, but in the hands of director Eastwood, screenwriter Helgeland, and actor Wanda De Jesus, who plays her, Graciela is a fully realized character, suffering a terrible loss, trying to do the right thing by pursuing justice for his sister. Her presence in the picture moves the story along but also deepens our understanding for McCaleb through her eyes, and gives greater purpose to his mission. It’s one thing to lay everything on the line for a ghost, another for a living person, whom you will have to face when this is all over. Their blossoming love story gives the investigation emotional stakes.

Much of what makes Blood Work a satisfying thriller is down to author Michael Connelly, who apparently hated Clint’s adaptation (according to the Screen Rant article above) so much, he killed the character off. In the novel, Connelly created a character of uncommon vulnerability and compassion amongst thriller genre protagonists, and plotted an air tight-mystery where the killer’s reveal matters to us for once.

At this point, if you haven’t seen the film, you should save this post to your Reading List and seek out the movie, because you are leaving the spoiler-free zone.

Last warning…

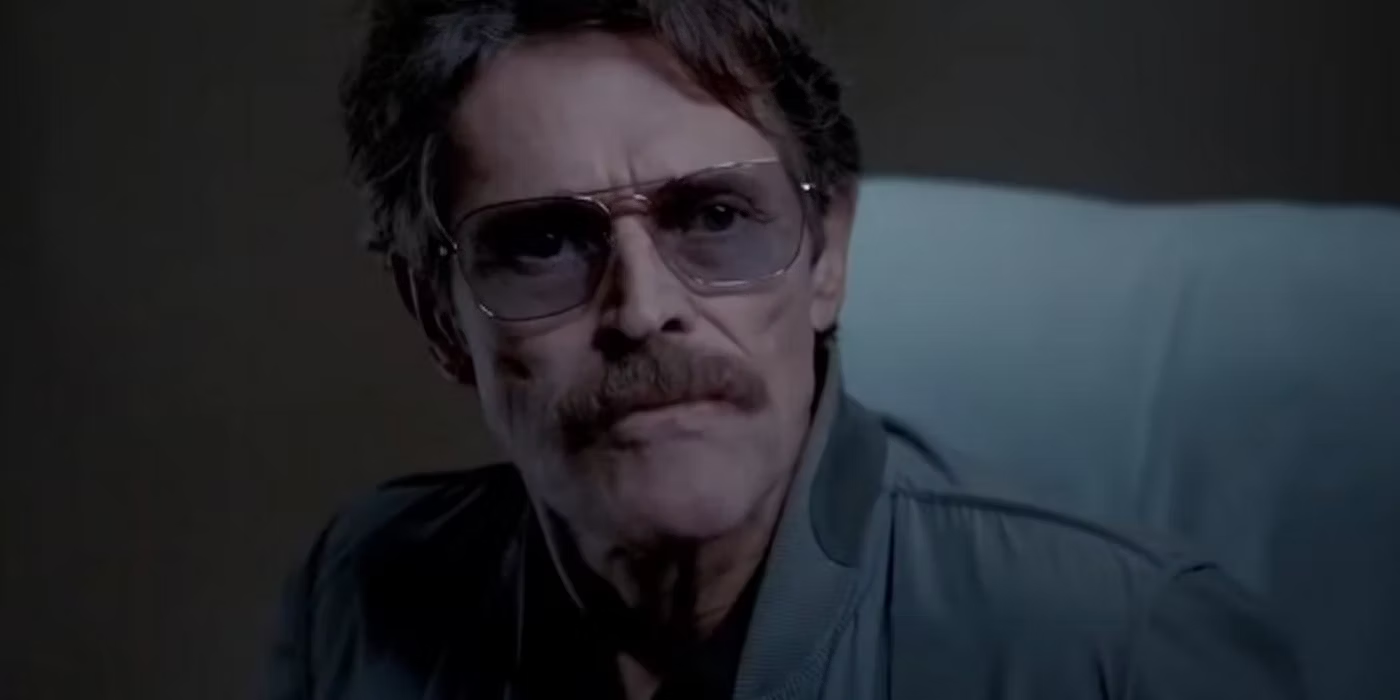

There is no way to talk about Jeff Daniels’ performance without addressing the fact that he is ultimately revealed to be the psycho killer behind the blood-stained love letters to McCaleb, and the long string of dead bodies he offers up like wilted roses in a perverse courtship. Which is what the killings amount to.

Buddy is a little like Jessica Walters’ deranged stalker-fan in Eastwood’s directorial debut, Play Misty For Me (1971): obsessed and delusional.

When Buddy is finally caught, he makes declarations straight out of the Jerry Maguire “You complete me” handbook.

Even though this is a thriller with Clint Eastwood, the character (of Buddy Noone) was like a distant cousin to Dumb & Dumber.

–Jeff Daniels on Blood Work.

Casting Daniels was a brilliant choice. Having long since established himself as an affable, non-threatening, light-comic leading man in pictures like Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1984) and Pleasantville (1998), as well as slapstick comedies like the Farrelly Brothers‘ Dumb & Dumber pictures, his presence in Blood Work as Clint’s funny sidekick made a lot of sense. But that well-established screen persona is used here as a smokescreen. Daniels is such a likeable performer, with such an air of decency and kindness, that the reveal of Buddy as the twisted serial killer is a total surprise. But Daniels seems to have so much fun once Buddy is unmasked, that the audience can’t help but have fun with him, too.

Take the scene where Buddy encounters the dead body of a murder victim and becomes visibly upset before having to walk away. This moment connives us that Buddy is a harmless, sensitive guy, and his revulsion at the killer’s violence speaks to our own. We identify more with Buddy than Clint’s tough-guy FBI profiler. Buddy is us. But of course Buddy’s reaction to the dead body is just a performance that he is putting on for McCaleb’s benefit (like everything else he does in the picture).

What really makes the twist work may not be evident upon first viewing, but on a second look, knowing that Buddy is the villain, you can see the slight undercurrent of menace and perversion to Daniels‘ performance. There is something creepy upon second viewing about the way that Buddy is overly concerned about McCaleb in all of their scenes together. Buddy is a little too invested in McCaleb’s well-being. When you know Buddy’s true intentions, his actions are all the more unnerving.

Following the reveal of the Code Killer’s true identity, the story becomes a more perfunctory plotting out of their inevitable confrontation.

But it is so gorgeously shot, with McCaleb slipping in and out of the shadows and fog of the marina at night, that you can forgive the simplicity of its narrative design.

This is where the film plays most like the closing chapter in the Dirty Harry saga. McCaleb isn’t here to make arrests. There’s nothing he wants more than a justifiable reason to pull the trigger on Buddy and close the book on the Code Killer once and for all.

You can’t help but anticipate McCaleb spitting out Dirty Harry’s trademark, “Make my day,” before Buddy does just that by pulling his machine gun.

McCaleb shows no hesitation or mercy. Like Det. Callaghan, he has no qualms about putting down a rabid dog, which is what a psychopathic killer like Buddy is to a man like McCaleb.

But it’s the water, not the bullets, that finally puts an end to the Code Killer. And not McCaleb’s hands…

But Graciela’s. She has avenged her sister’s killing. She is at peace.

One look at McCaleb tells us he is at peace, too. His mission is complete. He can move on with his life now and enjoy what’s left of it. And he won’t have to do it alone anymore, either.

This being a Clint Eastwood picture, in the end, the bad guys are punished (killed), order is restored, and the hero is rewarded for his bravery (violence).

When last we see him, McCaleb and his new love, Graciela, are literally sailing off into a perfect, golden sunset.

It’s a far cry from the sadistic head-in-box ending that Fincher gave us in Se7en.

If it never achieves Se7en’s lofty heights, or those of that other genre benchmark that has so rarely been equaled, Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, it still manages to rise above so many other lesser attempts to capture the magic of those two suspense classics (see: The Cell, Taking Lives, The Little Things, Longlegs, etc.).

You can tell when a scene is good. If you’re in the scene, and you’re playing the scene, you can tell when it’s working for all the characters. It can be difficult. Sometimes, when actors direct, when they are off camera, they start watching it, instead of participating in it. That can be a problem. You have to make sure you’re always throwing the switch.

–Clint Eastwood on directing himself.

Once again, Eastwood proves that no one since his mentor, the late, great Don Siegel (Dirty Harry; Escape From Alcatraz), directs him better than he does himself. He never attracts attention with frivolous framing or movement, but in the opening and closing chase sequences he proves that he’s as good a genre filmmaker as anybody.

And as an actor, Eastwood understands his relationship to the camera and to the audience. It may seem, superficially, that he is often playing the same character, but it is in the fine nuances and subtle variations on his screen persona that his skill as a performer really shines through. It reminds me of listening to Philip Glass’ music. Initially, all his compositions sound the same, but the more you listen, the more you hear and feel the impact of even the slightest variation on a melody. Blood Work may be a familiar tune, but it’s catchy, and you may find yourself humming it long after the picture is over.