Starring Jack Nicholson, David Morse, Anjelica Huston, Robin Wright, Priscilla Barnes, Piper Laurie, John Savage, Kari Wuher, Richard Bradford, Joe Viterelli, David Baerwald, Eileen Ryan, and Leo Penn.

Cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond.

Edited by Jay Cassidy.

Music by Jack Nitzsche.

Produced by David S. Hamburger.

Written, produced & directed by Sean Penn.

A Miramax release.

Like all of the greatest actors who distinguished themselves in the golden era of 1970s New Hollywood (Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Gene Hackman, etc), by the 1990s, Jack Nicholson was a bonafide movie star with a screen persona well established, polished, and refined over the decades. The distinction between “actor” and “movie star” is not meant to be pejorative. It is meant only to differentiate the roles in which, as younger men, they disappeared into their characters, and those in which, as older men, they were mostly vehicles that delivered what we had come to expect from them.

You can draw a line in the sand in De Niro’s career after Midnight Run (1988).

For Pacino, it’s Sea of Love (1989).

Hoffman, everything post-Rain Man (1988).

And the Gene Hackman of Loose Cannons (1990) was certainly not recognizable as the Popeye Doyle we know and love from both French Connection pictures.

But more than any of his contemporaries, Nicholson entered the 90s as a mega-star thanks to a little man-in-a-rubber-suit-picture you may, or may not, have heard of:

That isn’t to say that these movie stars never showed up as “actors” again. For each of them, it was mostly in supporting parts that they were able to continue the kind of character work they did in the 70s, and occasionally, they would still get lead role roles (usually in much more modestly budgeted pictures) that showed, not only that they still had it, but that “it” had matured, and ripened with age.

De Niro would have a Night and the City (1992), Mad Dog & Glory (1993), or a Copland (1997), for every Meet The Parents (2000), or Meet The Fockers (2004), or Little Fockers (2010) or Little Fockers (2010)

Pacino would use his Best Actor Oscar-clout from Scent of a Woman (1992) to direct and star in the celebrity-packed Looking for Richard (1996), his actors-putting-on-Shakespeare passion project, in between major studio releases, Heat (1995), and City Hall (1996).

Hoffman would star in small art-house fare like the adaptation of David Mamet’s American Buffalo (1996), and Barry Levinson’s political satire Wag The Dog (1997), also written by Mamet, in between pure genre excercises like Wolfgang Peterson’s prescient killler-virus thriller, Outbreak (1996), and Levinson’s Solaris-lite sci-fi mindfuck, Sphere (1998).

Hackman would use the movie star cred he earned from blockbuster box office hits like Tony Scott’s Crimson Tide (1995) and Enemy of the State (1998), to fuel Mamet’s Heist (2001), and did some of his best work ever in Wes Anderson’s third (and my favourite) feature, The Royal Tennenbaums (2001).

For my money, Nicholson’s best performance in the 90s, and my favourite of his from any era, a role which only Jack could have played, belongs to Sean Penn’s 1995 revenge-and-forgiveness drama, The Crossing Guard.

TCG was Penn’s second feature as writer-director, showing that his first, the searing, tragic family drama, The Indian Runner (1991), was no one-time fluke. With only two pictures under his director’s belt, Penn established himself as a genuine auteur, and one of the best American filmmakers of the decade.

Watch the video for Highway Patrolman on YouTube.

The story of the troubled relationship between two brothers (David Morse and Viggo Mortenson) on opposite sides of the law, Indian Runner was inspired by the lyrics to Bruce Springsteen’s Highway Patrolman from his Nebraska record (1982).

In an act of artistic reciprocity, The Boss would go on to pen the opening credits song, Missing, for The Crossing Guard.

Woke up this morning. There was a chill in the air.

Bruce Springsteen, Missing.

Went to the kitchen. My cigarettes were lying there.

Jacket hung on the chair the way I left it last night.

Everything was in place. Everything seemed all right.

…But you were missing.

Missing.

Last night I dreamed, the sky went black.

You were drifting down. Couldn’t get back.

Lost in trouble, so far from home.

I reached for you. My arms were like stone.

Woke, and you were missing.

Missing (x II)

Search for something, to explain.

In the whispering rain, and the trembling leaves.

Tell me baby, where did you go?

You were here just a moment ago.

There’s nights I still hear your footsteps fall.

And I can hear your voice, moving down the hall.

Drifting through the bedroom.

I lie awake but I don’t move.

In the opening scene, set at a group grief counselling session, we are introduced to Bobby, played by John Savage (The Deer Hunter; Do The Right Thing), who has lost his older brother.

It’s an excellent showcase for Savage, who never found the level of fame that his Deer Hunter castmates (Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken, and Meryl Streep) did. But with only this brief appearance in the opening scene, Savage makes an impression that lingers long after the picture is over.

As Bobby tells us, his deceased brother was the family favourite, “Son number 1.” Bobby was always “Son number 2,” but since his brother’s death, Bobby is “Son number 3,” a nickname for “Bobby, depressed.”

Bobby talks about the piece of himself that died along with his brother. “I miss me,” Bobby says. And that’s the hard truth people don’t talk about – how we become collateral damage when we lose a loved one, and how we have to find a way to mourn that lost version of ourselves.

That loss of self, and of all the collateral damage that follows in death’s wake, is beautifully articulated in brief testimonials from the other members of the therapy group (in what feels more like documentary than drama, but is no less affecting for it), is the true subject of Sean Penn’s haunting, thoughtful screenplay.

Though she doesn’t speak once in the scene, we experience this moment through the eyes of Mary, played by Anjelica Houston (her father, John Huston’s, Prizzi’s Honor; and The Dead), identified by on-screen text as “the mother.” Mary doesn’t need dialogue for us to know that Bobby’s words speak also for her. A solitary tear from a masterful performer like Huston says it all.

Nicholson stars as Freddy Gale, “the father,” a slightly shady downtown LA jeweler drowning himself in booze and strippers in the aftermath of his young daughter, Emily’s, death in a drunk driving incident.

Freddy spends most of his nights in a sleazy stripclub with his drunken, middle-aged loser buddies, in what feels like the 90s equivalent to Cosmo’s joint in John Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976).

Freddy has no time for group therapy. “I’m a busy man,” he tells us. “Always busy.” And besides that, Freddy has his own plan for combatting grief.

Freddy has marked his calendar. Today is the day the man who killed his daughter is being released from prison, and Freddy is going to kill him.

Played by The Indian Runner’s David Morse (12 Monkeys), John Booth is racked with crippling, gut-twisting guilt ever since accidentally killing Freddy’s and Mary’s little girl. His body may be getting out of prison, but his soul is another matter.

John doesn’t need Freddy to punish him, he’s happily taking care of that himself, as we see in an early flashback where John bashes his head against the bars of his cell, leaving him with a visible scar that can in no way compare to the invisible ones he shares with Freddy and Mary.

That’s the trouble with grief. You can’t see it. If we break our arm, we set the bone and wrap it in a cast. Everyone around us can see that we are injured, and healing. They know to take care around our broken parts. But with grief, there is no bone to set. Nothing to wrap a cast around. No sign of breakage. To everyone around us, we’re in perfect working condition. But we know better. Bobby already warned us.

Freddy, Mary, and John are all broken, but when Freddy shares his plan with Mary, his now ex-wife, remarried to Robbie Robertson (excellent in a rare dramatic performance), who is raising Freddy’s two young sons as if they were his own, she is less than grateful.

What does Freddy hope that murdering John Booth will accomplish? “Pride and relief,” he promises Mary.

Mary chides Freddy. She knows that killing Booth has nothing to do with honoring their dead daughter. It won’t bring her back. Freddy has never even had the courage to visit Emily’s grave.

Freddy returns to the strip joint, tries talking to his friends about his deteriorating mental state, but they laugh it off. Dismissed by Mary, and now by his pals, Freddy has nowhere to turn but to his ill-conceived plot for vengeance.

John Booth is surprisingly more receptive to Freddy’s plan. When he is confronted by Freddy sticking a gun in his face (fumbling and forgetting to load the weapon – Freddy is no practiced assassin), John seems to accept Freddy’s right to take revenge. We sense that he even welcomes it.

But he asks Freddy to take a couple of days to, “think about maybe not taking my life.” If, once those 72 hours are up, Freddy still wants to kill John, then he will be met with no resistance. “I’m not going anywhere,” John tells Freddy. “I’ll give you three days.” Freddy tells John. Maybe next time, Freddy will even remember to load his gun.

Of course, John is going somewhere. From the moment he is released from prison, he is on a collision course with Freddy. “Some lives cross,” the film’s poster tells us. “Others collide.”

The journey John and Freddy are now on can lead only to one of two places – either Freddy will follow through with his pledge to kill John, continuing the cycle of tragedy and grief that began with his daughter’s death, or somehow, through all of their shared suffering and pain, their inevitable collision will bring about catharsis and change. For both of them.

John has friends and parents who love him, and would mourn him. He doesn’t want to die, but he isn’t sure he deserves to live. He returns home having served his sentence with no greater plan than just to “get on with things.” And over the next 72 hours, he will do just that, knowing that they could be his last three days on the planet.

The events of those next three days will force Freddy, John, and Mary, to confront their guilt, grief, and anger head on. Will they be further casualties of the accident that killed poor little Emily, or will they survive, and by some miracle of the Gods of Forgiveness and Redemption, find peace?

John isn’t asking for anyone’s forgiveness, and he certainly isn’t expecting to find love, but when his best friend, Peter (David Baerwald), introduces him to the beautiful painter, Jo-Jo, at a welcome home party thrown in his honor, suddenly, John finds himself standing across from someone with enough empathy and compassion to see past the death and guilt that have come to define his life, preventing him from really living it.

Freedom is overrated.

John Booth, The Crossing Guard.

A conversation about compassion, and who does, and does not, deserve it, has the flow and feeling of documentary that the opening grief counselling session does. It’s a wonderfully staged, edited, and performed scene which gives John and Jo-Jo time and space to safely size each other up, and grow curious.

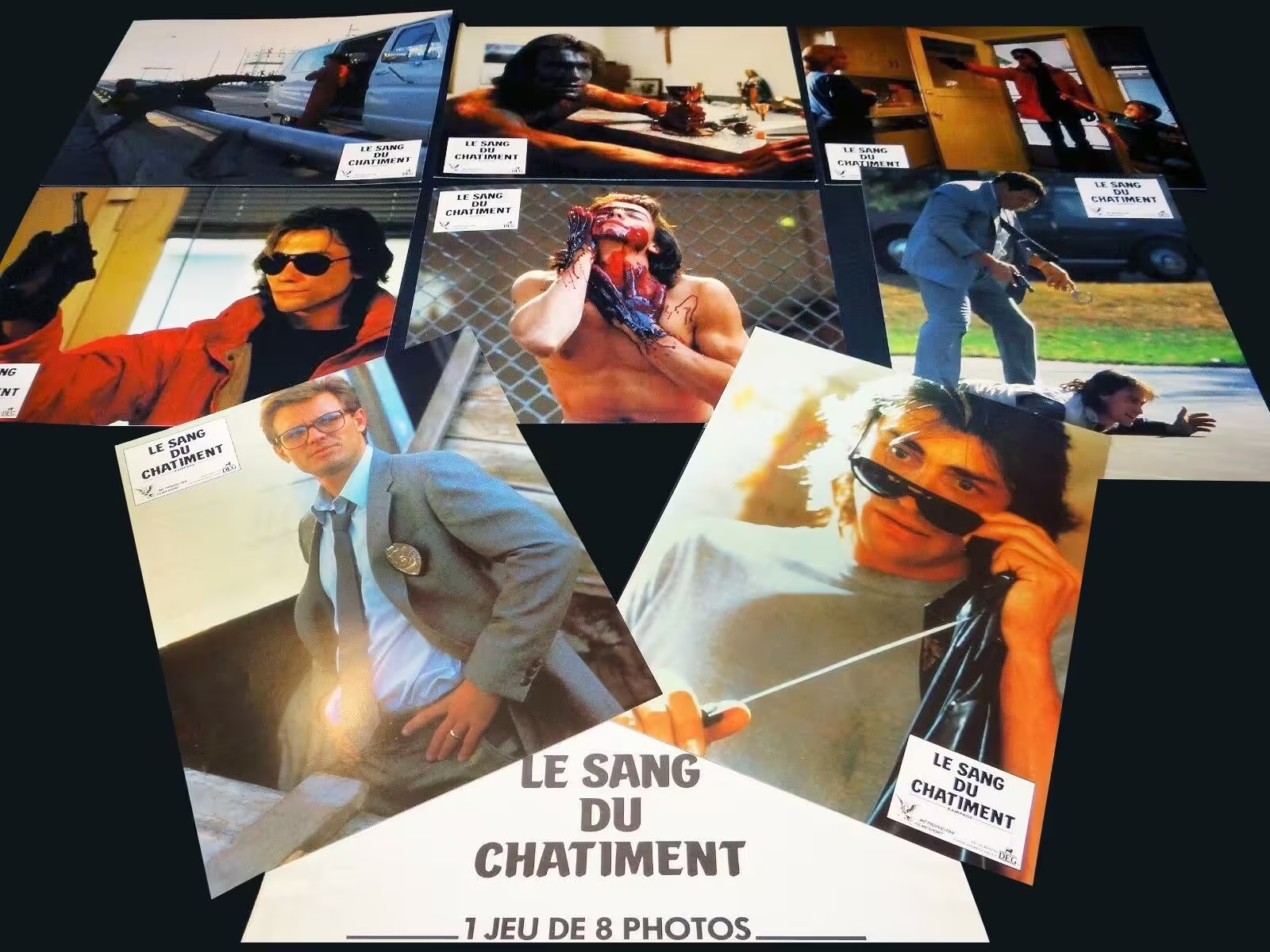

Wright (L) and Morse (R) in TCG.

Played by an excellent Robin Wright (The Princess Bride; Forrest Gump), reuniting with her past (State of Grace) and future (She’s So Lovely) co-star, and (now-ex) husband, Penn, Jo-Jo falls for John’s vulnerability, sees his pain, and offers him a port in the storm, a respite from his self-loathing.

Knowing that his days are literally numbered, John continues to sample the new life that awaits him, should Freddy choose to show him mercy, working on a fishing boat with Peter, who warns him that Jo-Jo is special, and to take care with her. “There are women and then there are ladies,” Peter tells John. “Jo-Jo is a lady.”

And as John builds bridges in his relationships, new and old, Freddy burns his own down.

Intercut with the welcome home party sequence, is one in which Freddy escorts a trio of exotic dancers from the club, including his long-suffering, on-again, off-again girlfriend, Verna (Mallrats’ Priscilla Barnes), to a classy restaurant, only to ruin dinner with a violent outburst that sees him arrested, finger printed, and having his mug shot taken, before the girls can bail him out the next morning.

“The father of the girl I killed threatened to kill me last night. You’re the only one I’ve told.”

John.

“Why me?“

Jo-Jo

“I thought it would be romantic.”

John

Finding no refuge at work, Freddy’s rage and hostility are seeping out of him.

He takes a little of that toxic bile of fury out on a dissatisfied customer, a ranting-racist played by Penn’s mother, Eileen Ryan.

Meanwhile, though Freddy has been unable to face his daughter’s grave, John visits with flowers.

There he finds Mary lost in thought, as her other children run around playing, without a care in the world. The sight of Emily’s grieving mother only further reminds John of all the pain he has caused and reinforces the idea that maybe his death really would be a fitting justice.

One of my favourite scenes in the picture is one in which a lonely, drunken Freddy visits a run down bar (brothel?) called Dreamland, where the patrons can dance with any of its “100 beautiful girls,” so long as they pay by the song.

A homeless man (played by Sean’s dad, Leo Penn) outside the bar warns Freddy not to enter Dreamland, “Unless you want to fall in love.”

My wife was a beautiful woman…

Freddy

…I met her in the sun… sun… sunny, sun…

Freddy

I could never fall in love at night.

Freddy

And so, immune to any nocturnal amorous temptations, Freddy stumbles into Dreamland, where he does not find love, though he does find a selection of emotionally vacant, but physically available, young “dance partners.”

Lit like subjects for a Caravaggio painting, as a Spanish cover of Aerosmith’s Love Hurts plays on the jukebox, the women’s faces all tell the same, sad, lonely story.

Even in the arms of the woman he dances with, Freddy is totally, completely alone. There is nothing holding him to the earth. No love to tether him. Only hate.

Meanwhile John continues to explore his blossoming romance with Jo-Jo, but his guilt, she tells him, is “a little too much competition.” If they are going to have any chance at a future together, John is going to have to let go of his suffering, and forgive himself.

Only then will John be free to accept love, from Jo-Jo, from his parents, or anyone else. “Let me know when you want life,” Jo-Jo says. But John doesn’t know how to let go of his self-loathing. He’s designated Freddy as his own personal St. Peter, and only Freddy has the power to absolve him. “What is guilt?” John asks Jo-Jo. She doesn’t have an answer. Instead, she asks him, “Do you want to dance?”

But Freddy, things will only get much darker before dawn.

In addition to an ex-wife, and a girlfriend, Freddy also has a mistress (Kari Wuher), Mia, a younger version of Verna, whom he tortures by openly flirting with Mia in front of her, even parading around on stage, to the wild amusement of his drinking buddies, as Verna looks on, trying, and failing, to hide her heartache, and Freddy takes no notice.

His dalliance with Mia proves more annoyance than distraction, as she (hilariously) serenades Freddy with a God-awful love song she has written just for him (“Freddy & Me-ee-ah,” she sings), and Freddy passes out, making him late for his date with John.

In a scene which should have netted them both Oscars, Freddy reaches out for one last desperate Hail Mary pass, calling his ex-wife after waking from a disturbing recurring nightmare.

Mary agrees to meet with Freddy, thinking that his vulnerability is proof that Freddy has turned a new leaf, but their reconciliation is short lived. Freddy’s rage returns, and so does Mary’s contempt.

Like something out of his nightmare, Freddy is haunted by the watchful gaze of a crossing guard as he drifts further away from mercy towards vengeance.

Today is judgement day.

John awaits Freddy’s arrival. There is no doubt that Emily’s father will come. Neither one of these men can escape the other’s trajectory. They are fated to make impact. But will they destroy each other? Or bring about each other’s salvation?

Freddy is delayed by a pair of LAPD officers, who pull him over for driving erratically. When he fails his roadside sobriety test, they attempt to make an arrest, but Freddy runs, and the police give chase.

Freddy reaches John’s trailer but finds John no longer content to play the martyr. John gets the drop on Freddy, pulling a rifle. But John doesn’t want to kill Freddy. And so, now it is John’s turn to run, and Freddy’s turn to chase.

But John isn’t running away from anything. He stops more than once to allow Freddy time to catch up. Rather, John is running to something.

At the gates to the cemetery where Emily is buried, Freddy catches up to John. And as the younger man scales the fence, Freddy takes aim and fires. He clips, but does not deter, John, who rises and continues on, ultimately, to Emily’s grave.

What transpires between them as they kneel before Emily’s pink stone, is one of the most empathetic moments of any film from the 90s, or any other decade. If revenge is swallowing poison hoping that the other person will die, then forgiveness is feeding the other guy medicine and discovering that you get well, too.

Through the road was paved with hate, it has led Freddy here, back to Emily, whose loss rendered him this dedicated husk of a man. But now his anger melts away. All that is left is his grief. Finally Freddy is ready to mourn his daughter. The road ahead is long. It stretches as far as the eye can see. But hate is no longer behind the wheel. There is room for love. For Freddy, and for John. Through Freddy’s forgiveness and mercy, John is now ready to forgive himself, too.

Dawn breaks. Mary, her husband and kids, Peter, John’s parents, and of course, Jo-Jo, will all soon be waking. Maybe now, in the light of a new day, Freddy and John will be ready to face them. They want life again.

The Crossing Guard is the type of character-driven, adult-themed drama that New Hollywood turned out like hotcakes in the years between Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and Heaven’s Gate (1980).

Penn’s choice of Vilmos Zsigmond as DOP ensured that TCG, at the very least, looked like one of those 70s masterpieces.

Zsigmond was responsible for lensing some of that decade’s most beautiful and iconic pictures, from Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), and The Long Goodbye (1973), to John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), Brian De Palma’s Obsession (1976), Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978).

And Penn’s selection of Jack Nitzsche to compose the score, made sure that TCG sounded like a long, lost 70s picture, too.

I first saw The Crossing Guard at TIFF, when it was still referred to as “The Festival of Festivals.” It was my first exposure to the film festival, or any film festival, for that matter, an exclusive gala screening at Toronto’s magnificent Roy Thompson Hall.

Sean Penn attended the gala to introduce his film and stepped on stage, smoking a cigarette (despite RTH being a strictly no-smoking venue), to declare that, although he wasn’t there in person, what the audience was about to see on screen represented Jack’s “blood, sweat, and tears.” Penn’s own blood, sweat, and tears were all over the screen, too. The film is all heart (and heartbreak).

Penn and Nicholson would reunite on the former’s next directorial effort, the very good The Pledge, another harrowing, emotional drama with exceptional performances (despite an unfortunately cast Benicio Del Toro as a mentally-diminished Indigenous man). But it is The Crossing Guard that I believe represents their greatest work together, and possibly their greatest work, full stop.

Penn famously took a three-year break from acting between 1990’s Irish-mob drama, State of Grace, and 1993’s melancholy gangster picture, Carlito’s Way, during which time he wrote and directed The Indian Runner.

Following The Pledge, Penn would have a hit with 2007’s Into The Wild, and a miss with 2016’s The Last Face. I’ve yet to see 2021’s Flag Day, but I have high hopes.

On screen, Penn followed The Crossing Guard with Oscar-nominations for Best Actor in Dead Man Walking (one of his best), the same year that TCG was released, and in 2002 for I Am Sam (not one of his best).

He won the gold statue twice, for Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River (2003), and Gus Van Sant’s Harvey Milk bio-pic Milk (2009).

Penn’s star has fallen somewhat in recent years, with pictures like The Gunman (2015), and Asphalt City (2023), failing to connect with either audiences or critics, but with the upcoming release of Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (2025), he may soon be on the precipice of a major acting comeback. Only time will tell if he has enough blood, sweat, and tears left to deliver another Crossing Guard.

And with Nicholson happily and officially retired since co-starring with Morgan Freeman in Rob Reiner’s The Bucket List (2007), I’m confident we will never see a greater performance from Jack than the one he gifted us with his portrayal of Freddy Gale in Penn’s excellent and criminally overlooked 90s masterpiece.

Like those great actors of the 70s, a period to which this film spiritually belongs, The Crossing Guard has only matured and ripened with age. It’s a film I intend to grow old with. As a 15 year-old falling in love with the movies for the first time, I didn’t just see this film, I collided with it.