*This post is dedicated to Watercat, who was able to source a copy of the film for me, a major blind spot in my Friedkin viewings.

Written, produced, and directed by William Friedkin (The French Connection, The Exorcist), this barely released, and still little seen serial killer thriller features one of Morricone’s most quietly unnerving scores.

The Album:

Listen to Morricone’s complete score for “Rampage” here:

RAMPAGE (FULL VINYL)

Purchase the vinyl at Discogs here:

The Film:

Synopsis from Miramax’s official site:

“Legal insanity is so often the default, modern-day defense for gruesome crimes and for Alex McArthur the claim is no different. Alex is an outwardly normal man who goes on incredible killing and mutilating sprees. When he is finally captured and brought to trial, the district attorney is torn between his own liberal ideals on guilt and personal responsibility, and the heinous crimes for which the accused is being tried.”

From Wikipedia:

“Rampage is a 1987 American crime drama film written, produced and directed by William Friedkin. The film stars Michael Biehn, Alex McArthur, and Nicholas Campbell. Friedkin wrote the script based on the novel of the same name by William P. Wood, which was inspired by the life of Richard Chase.[4]

The film premiered at the Boston Film Festival on September 24, 1987, but its theatrical release was stalled for five years due to production company and distributor De Laurentiis Entertainment Group going bankrupt. In 1992, Miramax obtained distribution rights and gave the film a limited release in North America. For the Miramax release, Friedkin reedited the film and changed the ending.

Plot summary

Charles Reece is a serial killer who commits a number of brutal mutilation-slayings in order to drink blood as a result of paranoid delusions. Reece is soon captured. Most of the film revolves around the trial and the prosecutor’s attempts to have Reece found sane and given the death penalty. Defense lawyers, meanwhile, argue that the defendant is not guilty by reason of insanity. The prosecutor, Anthony Fraser, was previously against capital punishment, but he seeks such a penalty in the face of Reece’s brutal crimes after meeting one victim’s grieving family.

In the end, Reece is found sane and given the death penalty, but Fraser’s internal debate about capital punishment is rendered academic when Reece is found to be insane by a scanning of his brain for mental illness. In the ending of the original version of the film, Reece is found dead in his cell, having overdosed himself on antipsychotics he had been stockpiling.

Alternate ending

In the ending of the revised version, Reece is sent to a state mental hospital, and in a chilling coda, he sends a letter to a person whose wife and child he has killed, asking the man to come and visit him. A final title card reveals that Reece is scheduled for a parole hearing in six months.

Cast

- Michael Biehn as Anthony Fraser

- Alex McArthur as Charlie Reece

- Nicholas Campbell as Albert Morse

- Deborah Van Valkenburgh as Kate Fraser

- John Harkins as Dr. Keddie

- Art LaFleur as Mel Sanderson

- Billy Greenbush as Judge McKinsey

- Royce D. Applegate as Gene Tippetts

- Grace Zabriskie as Naomi Reece

- Carlos Palomino as Nestode

- Roy London as Dr. Paul Rudin

- Donald Hotton as Dr. Leon Gables

- Andy Romano as Spencer Whaley

- Patrick Cronin as Harry Bellenger

- Whitby Hertford as Andrew Tippetts

- Brenda Lilly as Eileen Tippetts

- Roger Nolan as Dr. Roy Blair

- Rosalyn Marshall as Sally Ann

- Joseph Whipp as Dr. George Mahon

- Angelo Vitale as Assistant District Attorney

- Paul Gaddoni as Aaron Tippetts

Influences

Charles Reece is a composite of several serial killers,[5] and primarily based on Richard Chase.[6]

The crimes that Reece commits are slightly different from Chase’s, however; Reece kills three women, a man and a young boy, whereas Chase killed two men, two women (one of whom was pregnant), a young boy and a 22-month-old baby. Additionally, Reece escapes at one point—which Chase did not do—murdering two guards and later a priest. However, Reece and Chase had a similar history of being institutionalized for mental illness prior to their murders, along with sharing a fascination with drinking blood and cutting open the organs of their victims. Reece wears a bright colored ski parka during his murders and walks into the houses of his victims, as did Chase. The two also share the same paranoia about being poisoned. When Reece is incarcerated, he refuses to eat the prison food since he believes it has been poisoned, which mirrors the behavior of Chase in prison. who tried to get the food he was being served tested since he thought it was poisoned.[7][8] Unlike with Reece in the 1992 cut, Chase was sentenced to death, but he was found dead in his prison cell, an apparent suicide, before the sentence could be carried out.[9][10] In the early 1990s, Friedkin said he changed this detail of Chase’s life in the second cut since having him be released from prison fitted better with the traditions of the United States.[11] In both versions of the film, Reece lives with his mother and has a job. When Chase’s crimes were being committed, he lived alone in an apartment and was unemployed. Reece’s father is also said to have died when he was a child, whereas Chase’s father was still alive when his crimes were being committed.

While Chase was noted for having an unkempt appearance and exhibiting traits of paranoid schizophrenia in public, the film’s makers intended to portray Reece as “quietly insane, not visually crazed.”[5] Alex McArthur said in 1992 that “Friedkin didn’t want me to play the guy as a raging maniac. We tried to illustrate the fact that many serial killers are clean-cut, ordinary appearing men who don’t look the part. They aren’t hideous monsters.”[5] To prepare for the role, Friedkin introduced McArthur to a psychiatrist who deals with schizophrenics. He showed McArthur video tapes of interviews with different serial killers and other schizoids.[5]

The incident where Reece goes on a rampage after escaping custody was inspired by a real-life event in Illinois, that occurred while the film was in production.[5] In this event, the killer painted his face silver, something which Reece also does.[5]

The film had a negative portrayal of courtroom experts, and this was personally motivated by Friedkin’s ongoing custody battle for his son, which he was having with his ex-wife.[12]

Soundtrack

The film’s score was composed, orchestrated, arranged and conducted by Ennio Morricone and was released on vinyl LP, cassette and compact disc by Virgin Records.[13]

Release

Rampage was filmed in late 1986 in Stockton, California, where it had a one day only fundraising premiere at the Stockton Royal Theaters in August 1987. It played at the Boston Film Festival in September 1987, and ran theatrically in some European countries in the late 1980s. Plans for the film’s theatrical release in America were shelved when production studio DEG, the distributor of Rampage, went bankrupt. The film was unreleased in North America for five years.[14] During that time, director Friedkin reedited the film, and changed the ending (with Reece no longer committing suicide in jail) before its US release in October 1992.[2][15] The European video versions usually feature the film’s original ending. The original cut of the film has a 1987 copyright date in the credits, while the later cut has a 1992 copyright date, and includes new distributor Miramax‘s logo at the beginning, instead of DEG’s. The original cut also has the standard disclaimer in the credits about the events and characters being fictitious, unlike the later cut, which has a customized disclaimer, mentioning that it was partly inspired by real events.

In retrospect, William Friedkin said: “At the time we made Rampage, [producer] Dino De Laurentiis was running out of money. He finally went bankrupt, after a long career as a producer. He was doing just scores of films and was unable to give any of them his real support and effort. And so literally by the time it came to release Rampage, he didn’t have the money to do it. And he was not only the financier, but the distributor. His company went bankrupt, and the film went to black for about five years. Eventually, the Weinsteins’ company Miramax took it out of bankruptcy and rereleased it. But this was among the lowest points in my career.”[16] There was a year long negotiation with Miramax, and a disappointing test screening of the original cut. The changes that Friedkin made with the 1992 cut addressed concerns from Miramax that the film was not coherent enough, in addition to addressing Friedkin’s changing stance towards the death penalty.[12] The 1992 cut included a previously unreleased scene of Reece buying a handgun at the beginning and lying about his history of mental illness (just as Richard Chase did), whereas the original cut begins with one of Reece’s murders, without explaining any of his background.

Regarding the five year gap between the film’s American release, McArthur said in 1992: “It was a weird experience. First it was coming out and then it wasn’t, back and forth. The fact that it was released at all is amazing.” McArthur added that: “I’ve changed a lot since that picture was made. I have three children now and I’m not sure I would play the part today. I certainly wouldn’t want my kids to see it.”[5]

In 1992, the film played at 175 theaters in the United States, grossing roughly half a million dollars against a budget of several million dollars. McArthur said in 1992 that the film was never intended to be a big commercial hit.[5]

Reception

The film received a polarized response.[17][18] Some critics ranked Rampage among Friedkin’s best work.[2] In his review, film critic Roger Ebert gave Rampage three stars out of four, saying: “This is not a movie about murder so much as a movie about insanity—as it applies to murder in modern American criminal courts…Friedkin[‘s] message is clear: Those who commit heinous crimes should pay for them, sane or insane. You kill somebody, you fry—unless the verdict is murky or there were extenuating circumstances.”[19] Gene Siskel opined the film needed more scenes in the courtroom.[20] Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised the acting and commented: “Rampage has a no-frills, realistic look that serves its subject well, and it avoids an exploitative tone.”[21]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called the film “despicable”, saying that the “movie devolves into hateful propaganda” and “its muddled legal arguments come off as cover for a kind of righteous blood lust”.[22] Stephen King, an admirer of Rampage, wrote a letter to the magazine defending the film.[2]

Desson Howard of The Washington Post noted that in the film’s five year delay, there had been several high profile serial killer cases, saying: “In this Jeffrey Dahmer era, McArthur’s claims of unseen voices and delusions that he needed to replace his contaminated blood with others’ are familiar tabloid fare”, however, he noted that despite this, the film “still preserves a horrifying edge.”[23] In a separate 1992 review for The Washington Post, Richard Harrington had a more negative view, criticizing the film for feeling like a made for television feature, and claiming that it had a dated look to it due to its long delay.[24]

In retrospect, William Friedkin said: “There are a lot of people who [now] love Rampage, but I don’t think I hit my own mark with that”.[16] In another interview, Friedkin said he thought the film failed because audiences perceived it as being too serious, and they were expecting something different from him.[12]

In 2021, Patrick Jankiewicz of Fangoria wrote: “Half-serial killer thriller, half-courtroom drama, Rampage is an unnerving study on the nature of evil and what society should do about it.”[25]

Home media

Friedkin’s original cut featuring the alternate ending and some additional footage was released on LaserDisc in Japan only by Shochiku Home Video in 1990.[2]

The American edit of the film was released on LaserDisc in 1994 by Paramount Home Video.[2] The film received a DVD release by SPI International in Poland.[26]

Kino Lorber announced plans to release Rampage on Blu-ray in 4K UHD sometime in 2024.[27]

Bibliography

- Friedkin, William (2013). The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0061775123.

External links

- Rampage at IMDb

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› Rampage at AllMovie

- Rampage at the TCM Movie Database

- Rampage at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rampage at Box Office Mojo

- Director Friedkin Confronts Social Issues in Film at The Harvard Crimson

The Director:

From Wikipedia:

“William David Friedkin (/ˈfriːdkɪn/; August 29, 1935 – August 7, 2023) was an American film, television and opera director, producer, and screenwriter who was closely identified with the “New Hollywood” movement of the 1970s.[1][2] Beginning his career in documentaries in the early 1960s, he is best known for his crime thriller film The French Connection (1971), which won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and the horror film The Exorcist (1973), which earned him another Academy Award nomination for Best Director.

Friedkin’s other films in the 1970s and 1980s include the drama The Boys in the Band(1970), considered a milestone of queer cinema; the originally deprecated, now lauded thriller Sorcerer (1977); the crime comedy drama The Brink’s Job (1978); the controversial thriller Cruising (1980);[3][4] and the neo-noir thriller To Live and Die in L.A.(1985). Although Friedkin’s works suffered an overall commercial and critical decline in the late 1980s, his last three feature films, all based on plays, were positively received by critics: the psychological horror film Bug (2006), the crime film Killer Joe (2011), and the legal drama film The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (2023), released two months after his death. He also worked extensively as an opera director from 1998 until his death, and directed various television films and series episodes for television.

Early life and education

Friedkin was born in Chicago, Illinois, on August 29, 1935, the son of Rachael (née Green) and Louis Friedkin. His father was a semi-professional softball player, merchant seaman, and men’s clothing salesman. His mother, whom Friedkin called “a saint,” was a nurse.[5][6] His parents were Jewish emigrants from Ukraine, in the Russian empire.[7]His grandparents, parents, and other relatives fled Russia during a particularly violent anti-Jewish pogrom in 1903.[8] Friedkin’s father was somewhat uninterested in making money, and the family was generally lower middle class while he was growing up. According to film historian Peter Biskind, “Friedkin viewed his father with a mixture of affection and contempt for not making more of himself.”[5]

After attending public schools in Chicago, Friedkin enrolled at Senn High School, where he played basketball well enough to consider turning professional.[9] He was not a serious student and barely received grades good enough to graduate,[10] which he did at the age of 16.[11] He said this was because of social promotion and not because he was bright.[12]

Friedkin began going to movies as a teenager,[9] and cited Citizen Kane as one of his key influences. Several sources claim that Friedkin saw this motion picture as a teenager,[13] but Friedkin himself said that he did not see the film until 1960, when he was 25 years old. Only then, Friedkin said, did he become a true cineaste.[14] Among the movies that he also saw as a teenager and young adult were Les Diaboliques, The Wages of Fear (which many consider he remade as Sorcerer), and Psycho (which he viewed repeatedly, like Citizen Kane). Televised documentaries such as 1960’s Harvest of Shame were also important to his developing sense of cinema.[9]

Friedkin began working in the mail room at WGN-TV immediately after high school.[15] Within two years (at the age of 18),[16] he started his directorial career doing live television shows and documentaries.[17] His efforts included The People vs. Paul Crump(1962), which won an award at the San Francisco International Film Festival and contributed to the commutation of Crump’s death sentence.[16][18] Its success helped Friedkin get a job with producer David L. Wolper.[16] He also made the football-themed documentary Mayhem on a Sunday Afternoon (1965).[19]

Career

1965–1979

As mentioned in his voice-over commentary on the DVD re-release of Alfred Hitchcock‘s Vertigo, Friedkin directed one of the last episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1965, called “Off Season”. Hitchcock admonished Friedkin for not wearing a tie while directing.[20]

In 1965, Friedkin moved to Hollywood and two years later released his first feature film, Good Times starring Sonny and Cher. He has referred to the film as “unwatchable”.[21] Several other films followed: The Birthday Party, based on an unpublished screenplay by Harold Pinter, which he adapted from his own play; the musical comedy The Night They Raided Minsky’s, starring Jason Robards and Britt Ekland; and the adaptation of Mart Crowley‘s play The Boys in the Band.[22]

His next film, The French Connection, was released to wide critical acclaim in 1971. Shot in a gritty style more suited for documentaries than Hollywood features, the film won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.[23] Friedkin’s next film was 1973’s The Exorcist, based on William Peter Blatty‘s best-selling novel, which revolutionized the horror genre and is considered by some critics to be one of the greatest horror movies of all time. The Exorcist was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. It won for Best Screenplay and Best Sound. Following these two pictures, Friedkin, along with Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich, was deemed one of the premier directors of New Hollywood. In 1973, the trio announced the formation of an independent production company at Paramount Pictures, The Directors Company. Whereas Coppola directed The Conversation and Bogdanovich, the Henry James adaptation, Daisy Miller, Friedkin abruptly left the company, which was soon closed by Paramount.[24]

Friedkin’s later movies did not achieve the same success. Sorcerer (1977), a $22 million American remake of the French classic The Wages of Fear, co-produced by both Universal and Paramount, starring Roy Scheider, was overshadowed by the blockbuster box-office success of Star Wars, which had been released exactly one week prior.[23] Friedkin considered it his finest film, and was personally devastated by its financial and critical failure (as mentioned by Friedkin himself in the 1999 documentary series The Directors). Sorcerer was shortly followed by the crime-comedy The Brink’s Job (1978), based on the real-life Great Brink’s Robbery in Boston, Massachusetts, which was also unsuccessful at the box-office.[25]

1980–1999

In 1980, Friedkin directed an adaptation of the Gerald Walker crime thriller Cruising, starring Al Pacino, which was protested during production and remains the subject of heated debate. It was critically assailed but performed moderately at the box office.[26]

Friedkin had a heart attack on March 6, 1981, due to a genetic defect in his circumflex left coronary artery, and nearly died. He spent months in rehabilitation.[27] His next picture was 1983’s Deal of the Century, a satire about arms dealing starring Chevy Chase, Gregory Hines, and Sigourney Weaver.

In 1985, Friedkin directed the music video for Barbra Streisand‘s rendition of the West Side Story song “Somewhere“,[28] which she recorded for her twenty-fourth studio LP, The Broadway Album. He later appears as Streisand’s interviewer (uncredited) on the television special, “Putting It Together: The Making of the Broadway Album”.[29]

The action/crime movie To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), starring William Petersen and Willem Dafoe, was a critical favorite and drew comparisons to Friedkin’s own The French Connection (particularly for its car chase sequence), while his courtroom drama/thriller Rampage (1987) received a fairly positive review from Roger Ebert.[30] He next directed the cult classic horror film The Guardian(1990) and the thriller Jade (1995), starring Linda Fiorentino. Though the latter received an unfavorable response from critics and audiences, he said it was one of the favorite films he directed.[31]

*Before this post gets derailed into an Angie Everhart appreciation, we now return to Friedkin’s late-period career:

2000–2023

In 2000, The Exorcist was re-released in theaters with extra footage and grossed $40 million in the U.S. alone. Friedkin directed the 2006 film Bug due to a positive experience watching the stage version in 2004. He was surprised to find that he was, metaphorically, on the same page as the playwright and felt that he could relate well to the story.[32] The film won the FIPRESCI prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Later, Friedkin directed an episode of the TV series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation titled “Cockroaches”, which re-teamed him with To Live and Die in L.A. star William Petersen.[33] He directed again for CSI‘s 200th episode, “Mascara”.[34]

In 2011, Friedkin directed Killer Joe, a black comedy written by Tracy Letts based on Letts’ play, and starring Matthew McConaughey, Emile Hirsch, Juno Temple, Gina Gershon, and Thomas Haden Church. Killer Joe premiered at the 68th Venice International Film Festival, prior to its North American debut at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival. It opened in U.S. theaters in July 2012, to some favorable reviews from critics but did poorly at the box office, possibly because of its restrictive NC-17 rating. In April 2013, Friedkin published a memoir, The Friedkin Connection.[35] He was presented with a lifetime achievement award at the 70th Venice International Film Festival in September.[36] In 2017, Friedkin directed the documentary The Devil and Father Amorth about the ninth exorcism of a woman in the Italian village of Alatri.[37] In August 2022, it was announced officially that Friedkin would be returning to film directing to helm an adaptation of the two-act play The Caine Mutiny Court-Martialwith Kiefer Sutherland starring as Lt. Commander Queeg.[38] The film was completed before Friedkin’s death, and debuted in September 2023 in the out-of-competition category at the Venice Film Festival.[39]

Influences

Friedkin cited Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, François Truffaut, and Akira Kurosawa as influences.[40] Friedkin named Woody Allen as “the greatest living filmmaker”.[41]

In regard to influences of specific films on his films, Friedkin noted that The French Connection[‘s] documentary-like realism was the direct result of the influence of having seen Z, a French film by Costa-Gavras:

After I saw Z, I realized how I could shoot The French Connection. Because he shot Z like a documentary. It was a fiction film but it was made like it was actually happening. Like the camera didn’t know what was gonna happen next. And that is an induced technique. It looks like he happened upon the scene and captured what was going on as you do in a documentary. My first films were documentaries too. So I understood what he was doing but I never thought you could do that in a feature at that time until I saw Z.[42]

Z – 40th Anniversary Trailer

Personal life

Friedkin was married four times:

- Jeanne Moreau, married February 8, 1977, and divorced in 1979.[43][44]

- Lesley-Anne Down, married in 1982 and divorced in 1985.[45][46]

- Kelly Lange, married on June 7, 1987, and divorced in 1990.[47][48]

- Sherry Lansing, married on July 6, 1991.[49][50]

While filming The Boys in the Band in 1970, Friedkin began a relationship with Kitty Hawks, daughter of director Howard Hawks. It lasted two years, during which the couple announced their engagement, but the relationship ended about 1972.[51] Friedkin began a four-year relationship with Australian dancer and choreographer Jennifer Nairn-Smith in 1972. Although they announced an engagement twice, they never married. They had a son, Cedric, on November 27, 1976.[52][53] Friedkin and his second wife, Lesley-Anne Down, also had a son, Jack, born in 1982.[46] Friedkin was raised Jewish, but called himself an agnostic later in life, although he said that he strongly believed in the teachings of Jesus Christ.[54][55]

Death

Friedkin died from heart failure and pneumonia at his home in the Bel Air neighborhood of Los Angeles on August 7, 2023.[6][56]

Work

Film

Narrative films

| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Producer | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Good Times | Yes | Uncredited | No | [57] |

| 1968 | The Birthday Party | Yes | No | No | [58] |

| The Night They Raided Minsky’s | Yes | No | No | [57] | |

| 1970 | The Boys in the Band | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1971 | The French Connection | Yes | Uncredited | No | [57] |

| 1973 | The Exorcist | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1977 | Sorcerer | Yes | Uncredited | Yes | [57] |

| 1978 | The Brink’s Job | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1980 | Cruising | Yes | Yes | No | [57] |

| 1983 | Deal of the Century | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1985 | To Live and Die in L.A. | Yes | Yes | No | [57] |

| 1987 | Rampage | Yes | Yes | Yes | [57] |

| 1990 | The Guardian | Yes | Yes | No | [57] |

| 1994 | Blue Chips | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1995 | Jade | Yes | Uncredited | No | [57] |

| 2000 | Rules of Engagement | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 2003 | The Hunted | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 2006 | Bug | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 2011 | Killer Joe | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 2023 | The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial | Yes | Yes | No | [58] |

Documentary films

| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Producer | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | The People vs. Paul Crump | Yes | No | Yes | [57] |

| 1965 | The Bold Men | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| Mayhem on a Sunday Afternoon | Yes | No | Yes | [59] | |

| 1966 | The Thin Blue Line | Yes | Story | Yes | [57] |

| 1975 | Fritz Lang Interviewed by William Friedkin | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1986 | Putting It Together: The Making of the Broadway Album | Uncredited | No | No | [57] |

| 2007 | The Painter’s Voice | Yes | No | No | [60] |

| 2017 | The Devil and Father Amorth | Yes | Yes | No | [58] |

Television

TV series

| Year | Title | Episode | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | The Alfred Hitchcock Hour | “Off Season” (S3 E29) | [58] |

| 1967 | The Pickle Brothers | TV pilot (S1 E1) | [57] |

| 1985 | The Twilight Zone | “Nightcrawlers” (S1 E4c) | [64] |

| 1992 | Tales from the Crypt | “On a Deadman’s Chest” (S4 E3) | [58] |

| 2007 | CSI: Crime Scene Investigation | “Cockroaches” (S8 E9) | [58] |

| 2009 | “Mascara” (S9 E18) | [58] |

TV movies

| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Executive producer | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | C.A.T. Squad | Yes | No | Yes | [57] |

| 1988 | C.A.T. Squad: Python Wolf | Yes | Yes | Yes | [57] |

| 1994 | Jailbreakers | Yes | No | No | [57] |

| 1997 | 12 Angry Men | Yes | No | No | [58] |

Stage

Operas

| Year | Title and Composer | Country / Opera House | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Wozzeck, Alban Berg | Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Theatre | [65] |

| 2002 | Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, Béla Bartók | Los Angeles Opera | [66][67] |

| Gianni Schicchi, Giacomo Puccini | [66][67] | ||

| 2003 | La damnation de Faust, Hector Berlioz | [68] | |

| 2004 | Ariadne auf Naxos, Richard Strauss | [69][67] | |

| 2005 | Samson and Delilah, Camille Saint-Saëns | June, New Israeli Opera October, Los Angeles Opera | [67] |

| Aida, Giuseppe Verdi | Teatro Regio Torino | [70][71] | |

| 2006 | Salome, Richard Strauss | Bavarian State Opera | [72] |

| Das Gehege, Wolfgang Rihm | [73] | ||

| 2008 | Il tabarro, Giacomo Puccini | Los Angeles Opera | [74] |

| Suor Angelica, Giacomo Puccini | [74] | ||

| 2011 | The Makropulos Case, Leoš Janáček | Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Theatre | [75] |

| 2012 | The Tales of Hoffmann, Jacques Offenbach | Theater an der Wien | [72] |

| 2015 | Rigoletto, Giuseppe Verdi | Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Theatre | [76] |

Bibliography

- Friedkin, William. The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir. New York: HarperCollins, 2013. ISBN 978-0-06-177512-3

- Friedkin, William. Conversations at the American Film Institute With the Great Moviemakers: The Next Generation. George Stevens, Jr., ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012. ISBN 978-0-307-27347-5

The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir:

From the Amazon product page:

“’Friedkin’s book does the unthinkable: It relates the behind-the-scenes stories of his triumphs like The French Connection and The Exorcist, but also sees Friedkin take responsibility (brutally so) for his wrong calls. . . . In doing so, he captures the gut-wrenching shifts of a filmmaker’s life—the bizarre whipsaw from success to disaster.” —Variety

An acclaimed memoir from William Friedkin, a maverick of American cinema and Academy Award–winning director of such legendary films as The French Connection, The Exorcist, and To Live and Die in LA. The Friedkin Connection takes readers from the streets of Chicago to the suites of Hollywood and from the sixties to today, with autobiographical storytelling as fast-paced and intense as any of the auteur’s films.

Friedkin’s success story has the makings of classic American film. He was born in Chicago, the son of Russian immigrants. Immediately after high school, he found work in the mailroom of a local television station, and patiently worked his way into the directing booth during the heyday of live TV.

An award-winning documentary brought him attention as a talented new filmmaker and an advocate for justice, and it caught the eye of producer David L. Wolper, who brought Friedkin to Los Angeles. There he moved from television to film, displaying a versatile stylistic range. In 1971, The French Connection was released and won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and two years later The Exorcist received ten Oscar nominations and catapulted Friedkin’s career to stardom.

Penned by the director himself, The Friedkin Connection takes readers on a journey through the numerous chance encounters and unplanned occurrences that led a young man from a poor urban neighborhood to success in one of the most competitive industries and art forms in the world. In this fascinating and candid story, he has much to say about the world of moviemaking and his place within it.”

The Doc: “Friedkin Uncut”

Watch a trailer for the career-retrospective documentary “Friedkin Uncut” here:

Watch a long discussion with William Friedkin at the New York Film Academy here:

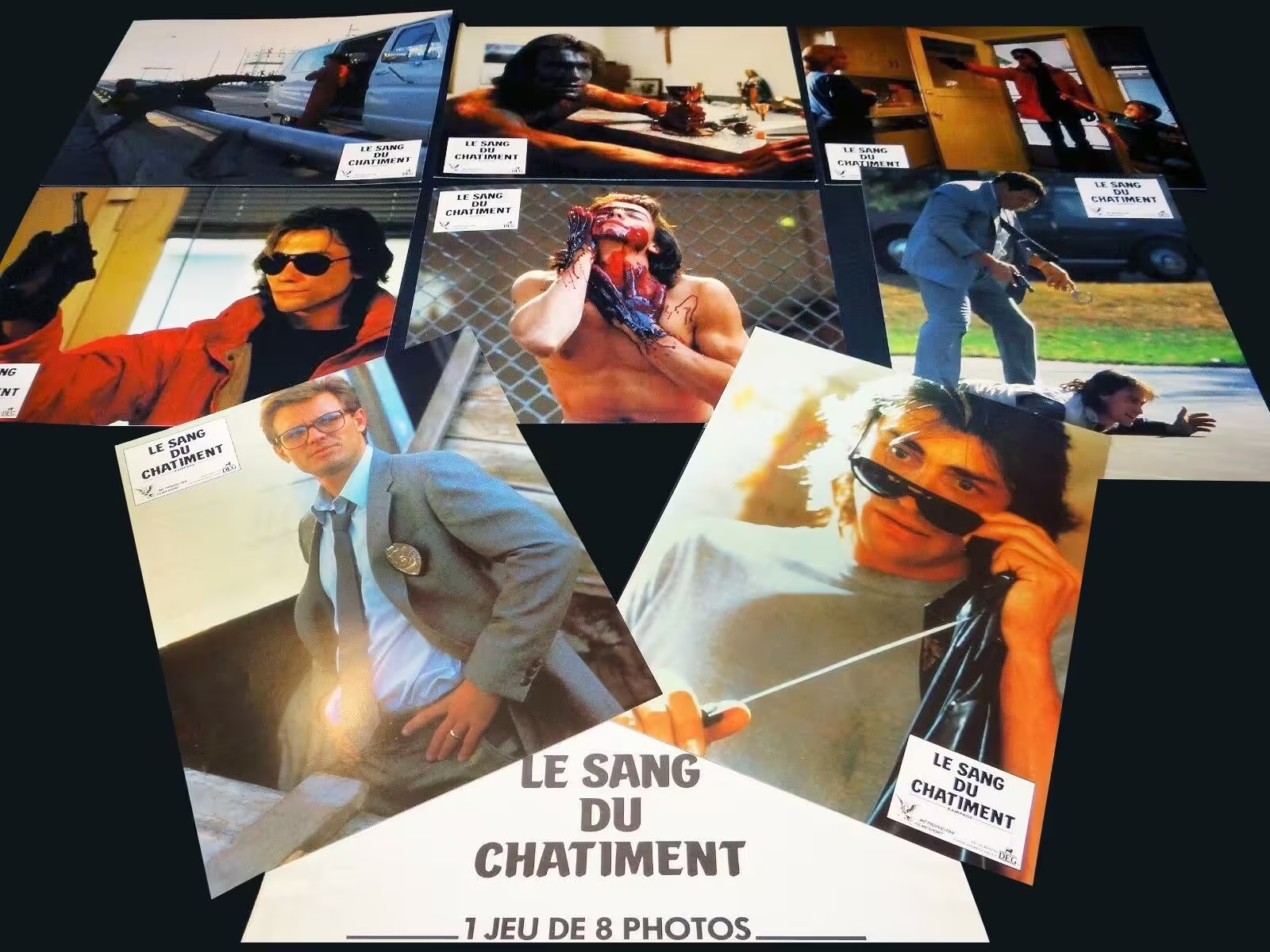

Film Posters:

Lobby Cards:

Home Video:

Ebert’s Take:

Still my favourite film lover, the late-great Roger Ebert.

“He is a pleasant-looking young man with a smile on his face…

…perhaps too bland a smile, as if he is not smiling about anything – as if the smile is a mask. He goes into a sports store to buy a gun, and makes small talk with the clerk, who apologizes that there is an obligatory waiting period. Hey, no problem! He comes back two days before Christmas to pick up his purchase, and then walks into a home and shoots people dead and carves out parts of their bodies with the precision of an experienced butcher.

The police, confronted by the murder scene, call it the work of a madman. A few days later, he strikes again, in broad daylight, walking into a home and butchering a woman while her helpless child looks on in terror. Nobody in his right mind could commit an act like this, without apparent motive or even with one. And yet the man, whose name is Charles Reece, is played by Alex McArthur as the kind of guy you’d see at a football game, or out washing his car. He doesn’t even make much of an attempt to evade discovery, wearing the same windbreaker to all of his crimes.

William Friedkin’s “Rampage” is based, the movie assures us, on a real story. We do not need the assurances. Serial killing is the crime of our times, and who knows what confluence of forces has led to these strange people who stare out at us from the covers of true crime paperbacks, their appearance as normal as their crimes are bizarre. Jeffrey Dahmer, a bystander said on television, looked like such a nice young man.

Friedkin tells the story of his killer more or less as a police procedural. We meet a cop (Michael Biehn) who tracks the killer, and then we see Reece captured by a simple means: He is identified by an eyewitness. Cornered at the gas station where he provides service with a smile, Reece leaps the back fence and runs away. The act of a reasonable man.

Eventually we see where Friedkin is going with the story.

This is not a movie about murder so much as a movie about insanity – as it applies to murder in modern American criminal courts. Friedkin plays with two decks and is happy to stack them both. His killer’s crimes are beyond our conception of possible human behavior, and then, in court, he is defended on the grounds that he must have been insane, and prosecuted on the grounds that he acted reasonably in so many other ways that he must have been sane. The difference between these two theories is the death penalty.

Friedkin does not quite say so in as many words, but his message is clear: Those who commit heinous crimes should pay for them, sane or insane. You kill somebody, you fry – unless the verdict is murky or there were extenuating circumstances. “Rampage” is not, however, a polemical film; it doesn’t press its points and doesn’t spend a lot of time on theory. It simply lays out the facts of a series of gruesome crimes, and then shows us how our gut feelings of good and evil grow confused after the testimony.

We are not much persuaded by the court arguments for either side. Friedkin wants it that way. Reece was sane, the prosecution argues, because he planned ahead to buy the gun and fled to avoid arrest. He was insane, the other side argues, because his crimes could not have been contemplated by a sane man. The prosecution offers an expert psychiatrist known as “Doctor Death” because of his invariable diagnosis of sanity. So it goes.

The film is realistic and matterof-fact, subdued compared to Friedkin’s great film of evil, “The Exorcist.” Alex McArthur, as the killer, is as unemotional and inoffensive as the protagonist of “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.” The movie was completed five years ago and then caught in the bankruptcy of the Dino De Laurentiis studio. Finally released, it has, if anything, benefited by the delay; five years ago, we would not have known how much Charles Reece resembles Jeffrey Dahmer, how little the face can reveal of the soul.”

Additional Links:

Watch the original 1987 VHS trailer for “Rampage” here:

Listen to Friedkin discussing his work with Morricone here:

Read Giant Freakin Robot’s re-appreciation of “Rampage” here:

Read Fangoria’s re-appreciation of “Rampage” here:

Purchase and download William Friendkin’s memoir, “The Friedkin Connection” from Amazon and Audible here:

Purchase a rare copy of the original screenplay for “Rampage” here:

Download the film for free at wipfilms.net

References (The Film)

- Knoedelseder Jr., William K. (August 30, 1987). “Producer’s Picture Darkens”. Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- Kelley, Bill (December 6, 1992). “Delayed ‘Rampage’ a “New” Serial Killer Film is Actually a Re-Cut Version of a Movie Shelved for Six Years”. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- Rampage at Box Office Mojo

- Liebenson, Donald (June 18, 1993). “But Soft, Friedkin Speaks”. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- “Alex McArthur starred in ‘Rampage’ five years ago and… – UPI Archives”.

- “The Vampire of Sacramento Richard Trenton Chase”. Haunted America Tours. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- Sullivan, Kevin (2012). Vampire: The Richard Chase Murders. WildBlue Press. ISBN 978-1942266112.

- Ressler, Robert; Thomas Schachtman (1992). Whoever Fights Monsters: My Twenty Years Tracking Serial Killers for the FBI(First ed.). St. Martin’s. p. 14. ISBN 0-312-07883-8.

- “Richard Trenton Chase – Crime Library”. truTV.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- Friedkin 2013, pp. 396–401.

- Friedkin, William

- Horn, D. C. (2023). The Lost Decade: Altman, Coppola, Friedkin and the Hollywood Renaissance Auteur in the 1980s. United States: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- “Ennio Morricone – Rampage (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)”. Discogs. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- “Friedkin vs. Friedkin: RAMPAGE Revisited”. Video Watchdog. No. 13. September 1992. p. 36.

- Friedkin 2013, pp. 400–401.

- Ebiri, Bilge (May 3, 2013). “Director William Friedkin on Rising and Falling and Rising in the Film Industry”. Vulture. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013.

- Dry, Sarah C. (October 29, 2002). “AN EYE FOR AN EYE: “Rampage” Shows the Horror of Murder”. The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- Terry, Clifford (October 30, 1992). “From mad to worse”. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- Ebert, Roger (October 30, 1992). “Rampage”. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 28, 2017 – via RogerEbert.com.

- Siskel, Gene (October 30, 1992). “Friedkin’s ‘Rampage’ Skims Surface of Provocative Subject”. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- Maslin, Janet (October 30, 1992). “Review/Film; Random Murder Spree In a Friedkin Thriller”. The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- Gleiberman, Owen (November 6, 1992). “Rampage (1992)”. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 20, 2007. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/rampagerhowe_a0af2c.htm [bare URL]

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/rampagerharrington_a0ab4d.htm [bare URL]

- Jankiewicz, Patrick (April 28, 2021). “William Friedkin’s RAMPAGE: How An Underrated Modern Serial Killer Thriller Was Lost And Found”. Fangoria. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- “Rampage (DVD) Michael Biehn McArthur William Friedkin PL IMPORT”. Amazon. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- Hamman, Cody (December 28, 2023). “Rampage: William Friedkin serial killer thriller is getting a 4K UHD release”. JoBlo.com. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

References (Friedkin)

- “The American New Wave: A Retrospective | H-Announce | H-Net”. networks.h-net.org. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- “June 1977: When New Hollywood Got Weird”. The Film Stage. June 21, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- “The Controversy of CRUISING | Cinematheque”. cinema.wisc.edu. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Guthmann, Edward (1980). “THE CRUISING CONTROVERSY: William Friedkin vs. the Gay Community”. Cinéaste. 10 (3): 2–8. JSTOR 41685938.

- Biskind, p. 200.

- Bahr, Lindsey (August 7, 2023). “William Friedkin, Oscar-winning director of ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The French Connection,’ dead at 87”. AP News. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- Pfefferman, Naomi. “‘Killer Joe’s’ William Friedkin: ‘I Could Have Been a Very Violent Person’.” Jewish Journal. August 2, 2012.Archived August 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Accessed April 29, 2013.

- Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection, p. 1.

- Biskind, p. 201.

- Segaloff, p. 25.

- Wakeman, p. 372.

- Friedkin, Conversations at the American Film Institute…, p. 186.

- Emery, p. 237; Claggett, p. 3.

- Friedkin, The Friedkin Connection, p. 9.

- Stevens, p. 184.

- Walker and Johnson, p. 15.

- Derry, p. 361; Edmonds and Mimura, p. 211.

- Hamm, p. 86-87.

- Charles Champlin, “Friedkin Damns the Torpedoes”, The Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1967. Retrieved via Newspapers.com.

- “Vertigo: The Legacy Series” Universal, 2008

- The Directors: William Friedkin

- Friedkin, William (2008). The Boys in the Band (Interview)(DVD). CBS Television Distribution. ASIN B001CQONPE. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Lee, Benjamin (August 7, 2023). “William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist and The French Connection, dies at 87”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- Bart, Peter (May 9, 2011). Infamous Players: A Tale of Movies, the Mob, (and Sex). Weinstein Books.

- Knoedelseder, William (August 30, 1987). “De Laurentiis: Producer’s Picture Darkens”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Segaloff, Nat (January 1, 1990). Hurricane Billy: The Stormy Life and Films of William Friedkin. New York: William Morrow & Co. ISBN 9780688078522.

- Biskind, p. 413.

- Howe, Matthew (2023). “Streisand Music Videos – “Somewhere” (1985)”. Barbra Archives. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Howe, Matthew. “Streisand/Television – “Putting It Together: The Making Of The Broadway Album” (1986)”. Barbra Archives. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Ebert, Roger (October 30, 1992). “Rampage”. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- William, Linda Ruth (2005). The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Indiana University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-253-21836-5.

- “EXCL: Bug Director William Friedkin”. May 18, 2007.

- Dimond, Anna (January 28, 2008). “CSI Exclusive: The Secrets Behind This Week’s Repeat”. TV Guide. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Chamberlin, James (April 3, 2009). “CSI: “Mascara” Review”. IGN. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Friedkin, William. The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir. New York: HarperCollins, 2013.

- “William Friedkin to receive Venice honour”. BBC News. May 2, 2013.

- Friedkin, William (October 31, 2016). “The Devil and Father Amorth: Witnessing “the Vatican Exorcist” at Work”. Vanity Fair.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (August 29, 2022). “William Friedkin Directing Kiefer Sutherland In Update Of Herman Wouk’s ‘The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial’ For Showtime & Paramount Global”. Deadline Hollywood.

- Buchanan, Kyle (August 7, 2023). “William Friedkin’s Final Film to Premiere at the Venice Film Festival”. The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Mike Fleming Jr (August 6, 2015). “William Friedkin Q&A: ’70s Maverick Revisits A Golden Era With Tales Of Glory And Reckless Abandon”. Deadline. Deadline Hollywood, LLC. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

Friedkin: “…. But none of us in the 70s thought we were operating in a golden age; we all had been influenced by Godard, Fellini, Truffaut, Kurosawa.”

- “William Friedkin on Woody Allen”. Youtube. May 21, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- “William Friedkin’s Favorite Films of all Time”. Fade In Magazine. June 12, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2022 – via YouTube.

- Martin, Judith. “Personalities.” Washington Post. February 9, 1977, p. B3.

- “Filing for Divorce.” Newsweek. June 25, 1979, p. 99.

- Sanders, Richard. “Director Billy Friedkin and Lesley-Anne Down Make a Home Movie-Divorce Hollywood Style.” People.September 2, 1985. Accessed April 29, 2013.

- “Names in the News.” Associated Press. August 15, 1985.

- “Director William Friedkin Marries News Anchor Kelly Lange.” Ocala Star-Banner. July 29, 1987, p. 2A. Accessed April 29, 2013.

- Ryon, Ruth. “Still Anchored in the Hills.” Los Angeles Times.May 31, 1992. Accessed April 29, 2013.

- Anderson, Susan Heller. “Chronicle.” New York Times. July 11, 1991. Accessed April 29, 2013.

- Teetor, Paul. “‘The Exorcist’ Director William Friedkin Tells All in His No-Bullshit Memoir.” Los Angeles Times. April 11, 2013.Archived April 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Accessed April 29, 2013.

- Segaloff, p. 98.

- (* 1976) “William Friedkin – Biography”. Movies.Yahoo.com. 2013. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “Failing Better Every Time.”, Sunday Independent. July 1, 2012.

- The Exorcist & The French Connection Dir. William Friedkin on Religion, Crime & Film on YouTube

- Brent Lang (April 12, 2013). “Director William Friedkin on Clashes With Pacino, Hackman and Why an Atheist Couldn’t Helm ‘Exorcist'”. The Wrap. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

My personal beliefs are defined as agnostic. I’m someone who believes that the power of God and the soul are unknowable, but that anybody who says there is no God is not being honest about the mystery of fate. I was raised in the Jewish faith, but I strongly believe in the teachings of Jesus.

- Dagan, Carmel (August 7, 2023). “William Friedkin, ‘The Exorcist’ Director, Dies at 87”. Variety. Retrieved August 7,2023.

- “William Friedkin”. BFI. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “William Friedkin – Rotten Tomatoes”. rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “Pro Football: Mayhem on a Sunday afternoon”. Torino Film Fest. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Muchnic, Suzanne (June 5, 2007). “KCET to air ‘The Painter’s Voice'”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Steen, Theodoor (August 14, 2023). “Sound And Vision: William Friedkin”. Screen Anarchy. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- O’Connor, John J. (January 10, 1986). “Streisand on Making Her Album”. The New York Times. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Kohn, Eric (October 27, 2017). “‘The Exorcist’ Director William Friedkin Has Never Seen the Sequels or Series, but He Loved ‘It’ — Q&A”. IndieWire. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- “Nightcrawlers – episode of The Twilight Zone”. Torino Film Fest. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Fabrikant, Geraldine (September 20, 2006). “At the Opera House, the Friedkin Connection”. The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Oxman, Steven (June 3, 2002). “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle/Gianni Schicchi Duke Bluebeard’s Castle/ Gianni Schicchi”. Variety. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Pasles, Chris (April 6, 2004). “L.A. to share ‘Samson’ with Israelis”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Variety Staff (September 14, 2003). “Celebs gather for ‘Faust’ fest”. Variety.

- Ginell, Richard S. (September 13, 2004). “Ariadne Auf Naxos”. Variety. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Luraghi, Silvia (October 25, 2015). “A successful Aida revival in Turin”. The Opera Critic. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Salazar, Francisco (February 23, 2023). “Teatro Regio di Torino Announces Cast Change for ‘Aida'”. OperaWire. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Daunt, Tina (March 22, 2012). “William Friedkin’s Latest Opera a Viennese Hit”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Ashley, Tim (November 2, 2006). “Das Gehege/Salome, Nationaltheater, Munich”. The Guardian. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- Swed, Mark (September 8, 2008). “‘Il Trittico,’ the Los Angeles Opera”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 26,2022.

- Aftab, Kareem (June 8, 2012). “William Friedkin: ‘We don’t set out to promote violence'”. The Independent. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- “Fall Classical Music In Florence”. Magenta Florence. October 4, 2015.

- Rich, Frank (December 18, 1981). “STAGE: ‘DUET FOR ONE,’ MUSICIAN’S STORY, AT ROYALE”. The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- “Duet for One (Broadway, Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, 1981) | Playbill”. Playbill.

- “AFI|Catalog – Gunn”. AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- “AFI|Catalog – Chastity”. AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- Winkler, Irwin (2019). A Life in Movies: Stories from Fifty Years in Hollywood. New York: Abrams Press. pp. 525–726. ISBN 9781419734526.

- “Daily News from New York, New York”. New York Daily News. January 20, 1970. p. 47.

Production Merger Phil D’Antoni and William Friedkin have joined forces with Milton Berle Paul W. Benson Productions to do the film version of “The Brass Go-between,” a novel by Oliver Bleeck. The suspense-thriller will be shot on locations in Washington, D.

- “3 FILMS ANNOUNCED BY DIRECTORS GROUP”. The New York Times. September 6, 1972. p. 40.

- Pinnock, Tom (October 19, 2012). “Peter Gabriel: “You could feel the horror…””. Uncut. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

I had written a short story on [the sleeve of] Genesis Live – one of the stories I used to tell onstage – and William Friedkin, who was the king of Hollywood because of The Exorcist, wanted me to work with him. Not as a musician, but as a screenwriter and ideas man. That was very exciting to me. In the end, unfortunately, nothing happened; it was one of many Hollywood projects that bit the dust.

- Easlea, Daryl (November 18, 2020). “Genesis, Peter Gabriel, and the story of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway”. Louder. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- Winning, Josh (January 1, 2009). “The Best Films Never Made”. Josh Winning. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- Clagett, Thomas D. (August 1, 2002). William Friedkin: Films of Aberration, Obsession and Reality. Los Angeles, Calif.: Silman-James Press. ISBN 9781879505612.

- Cagliari, Via. “Fritz Lang Interviewed by William Friedkin”. torinofilmfest.org. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- Phegley, Kiel (May 21, 2010). “Ellison Gets In “The Spirit””. Comic Book Resources. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- Buckley, Tom (December 15, 1978). “At the Movies”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Maslin, Janet (September 18, 1979). “Friedkin Defends His ‘Cruising'”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Buckley, Tom (October 5, 1979). “At the Movies”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- Riordan, James (September 1996). Stone: A Biography of Oliver Stone. New York: Aurum Pres. p. 308. ISBN 1-85410-444-6.

- Bach, Steven (1985). Final Cut: Dreams and Disaster in the Making of Heaven’s Gate. New York: New American Library. p. 379. ISBN 0451400364.

- Suplee, Curt (June 7, 1981). “The Passion of the Producer”. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- “‘Championship Season’ To Be Made Into Movie”. The New York Times. July 6, 1981. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- “”It’s The Smiles That Keep Us Going” : “The Exorcist III” at 30″. The Spool. August 17, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- Hefner, Hugh M., ed. (January 1, 1981). Playboy Magazine, July 1981. Playboy.

- Dunlevy, Dagmar (September 13, 1984). “Spielt in einem heißen Krimi: Laura Branigan”. Bravo (in German).

- “AFI|Catalog – To Live and Die in L.A.” AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- Cockrell, Eddie (July 25, 1985). “Film Talk”. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

- “SHOOTING OF STALLONE FILM RESCHEDULED”. Chicago Tribune. June 23, 1988. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- “The cut in execute”. Pop Cult Master. September 3, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Broeske, Pat H. (October 7, 1990). “Look Who’s Back With a New Movie: ‘The Deer Hunter’ made Michael Cimino a winner, but his next film was the legendary failure ‘Heaven’s Gate.’ With ‘Desperate Hours,’ the stakes have never been higher”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Broeske, Pat H. (November 12, 1989). “Upbeat, Downbeat”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Harrington, Richard (December 13, 1989). “ON THE BEAT”. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Marx, Andy (August 23, 1993). “Blatty, Friedkin reteaming”. Variety. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Pond, Steve (August 27, 1993). “SPIRITED REUNION”. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Cox, Dan (April 17, 1995). “Hopkins commits to ‘Jack the Ripper'”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Sandler, Adam (May 5, 1997). “New Line, Katja named in Ripper suit”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Fleming, Michael (March 25, 1997). “Friedkin holding the ‘Bag'”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Petrikin, Chris (March 10, 1998). “Friedkin set to tell ‘Truth'”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Variety Staff (March 18, 1998). “Rhames: from ‘King’ to ring”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Zoromski, Brian (October 13, 2000). “William Friedkin Reveals Details on His Upcoming Projects in IGN FilmForce’s Chat”. IGN. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- McNary, Dave (May 10, 2004). “Liston bio punched up”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- “William Friedkin (II)”. The Guardian. October 22, 1998. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- Bing, Jonathan (April 11, 2000). “Friedkin, Seven Arts circle Collins’ Mideast material”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Archerd, Army (September 6, 2001). “Helmer Friedkin to take on Hack’s Hughes”. Variety. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- Landau, Benny (August 30, 2002). “He’s Got the Keys to the Kingdom”. Haaretz. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- B., Scott (March 11, 2003). “An Interview with William Friedkin”. IGN. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Macnab, Geoffrey (December 19, 2003). “William Friedkin: The Devil in Mr Friedkin”. The Independent. Retrieved July 23,2023.

- Archerd, Army (May 14, 2003). “Zanuck advises Polanski on next move”. Variety. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

Friedkin will direct a movie based on an incident in Puccini’s life — the pic to star Placido, who will be needed (he’ll also sing) for three months on the pic!

- McNary, Dave (August 3, 2003). “‘Skulls’ in session for Paramount”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- B., Brian (July 27, 2004). “Terry Hayes to pen Book of Skulls”. MovieWeb. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Waxman, Sharon (February 9, 2004). “A Director, Married to the Studio; With a New Assignment from Paramount, Cries of Nepotism Dog William Friedkin”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Leffler, Rebecca (May 1, 2007). “Friedkin walks runway for Chanel biopic”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 23,2023.

- “Mikkelsen Joins Friedkin’s Coco & Igor”. ComingSoon.net. May 24, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Fischer, Russ (October 7, 2010). “William Friedkin Preparing To Film Another William Peter Blatty Adaptation?”. /Film. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- Sneider, Jeff (May 2, 2012). “Demian Bichir lines up pair of projects”. Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Jagernauth, Kevin (May 2, 2012). “Demian Bichir Follows Oscar Nom With Roles In ‘Machete Kills’ & William Friedkin’s ‘Trapped'”. IndieWire. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- “IamA Hollywood film director (Killer Joe, the Exorcist, French Connection). I’m William Friedkin. AMA”. May 24, 2012.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (September 11, 2012). “Toronto: Nicolas Cage Back With Emmett/Furla For ‘I Am Wrath'”. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- Jagernauth, Kevin (February 19, 2013). “Nicolas Cage Says ‘I Am Wrath’ With William Friedkin Is Not Happening, Reveals Dream Project With Roger Corman”. IndieWire. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- Kiang, Jessica (July 21, 2014). “Interview: William Friedkin on ‘Sorcerer,’ The ‘Killer Joe’ TV Show And Life Beyond “Macho Bullsh*t Stories””. IndieWire. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- Hiler, James (December 10, 2013). “Bette Midler to Star in ‘Mae West’ for HBO Films, William Friedkin Directing”. IndieWire. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- @nlyonne (August 7, 2023). “I ♥️ you, #WilliamFriedkin & will cherish this bad boy for always” (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Couch, Aaron (August 8, 2023). “‘Exorcist’ Stars Ellen Burstyn and Linda Blair Remember William Friedkin: “Undoubtedly a Genius””. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- Jagernauth, Kevin (June 9, 2014). “TV Shows Based On William Friedkin’s ‘Killer Joe’ & ‘To Live And Die in L.A.’ Developing”. IndieWire. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- Andreeva, Nellie (June 25, 2015). “‘To Live And Die In L.A.’ Series From William Friedkin & Bobby Moresco In Works At WGN America”. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- Mikulec, Sven (December 7, 2015). “A Discussion with William Friedkin: ‘I See a Diminishing of All Art Forms These Days'”. Cinephilia & Beyond.

- Kohn, Eric (October 23, 2017). “William Friedkin Is Developing ‘Killer Joe’ TV Series With ‘Million Dollar Baby’ Producer — Exclusive”. IndieWire. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (August 7, 2023). “Remembering William Friedkin: ’70s Maverick’s Death Defying Tales Making ‘The French Connection,’ ‘The Exorcist,’ ‘Sorcerer,’ To Live & Die In LA’ & Others In No Holds Barred Q&A”. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- Olson, Josh; Dante, Joe. “William Friedkin – The Movies That Made Me – Trailers From Hell”. Trailers from Hell (Podcast).

- Gallo, Phil (July 7, 2008). “Friedkin to direct ‘Truth’ at La Scala”. Variety. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Vivarelli, Nick (January 30, 2009). “Friedkin departs ‘Inconvenient’ opera”. Variety. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Purcell, Carey (December 17, 2013). “The Birthday Party, Starring Frances Barber, Steven Berkoff, Tim Roth and Nick Ullett, to Play the Geffen Playhouse”. Playbill. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Purcell, Carey (January 31, 2014). “Geffen Playhouse Postpones Revival of The Birthday Party”. Playbill. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- “1972 | Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences”. www.oscars.org. October 5, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “AFI Catalog of Feature Films: The First 100 Years 1893–1993 – The French Connection (1971)”. AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- “Winners & Nominees 1972”. Golden Globes. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “Film in 1973 | BAFTA Awards”. awards.bafta.org. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “1974 | Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences”. www.oscars.org. October 4, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “26th Annual DGA Awards Honoring Outstanding Directorial Achievement for 1973”. dga.org. Directors Guild of America. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- “Winners & Nominees 1974”. Golden Globes. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- Wilson, John (August 23, 2000). “Razzies.com – Home of the Golden Raspberry Award Foundation”. razzies.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved August 8,2023.

- “Past Winners Database”. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006.

- “50th Annual DGA Awards Honoring Outstanding Directorial Achievement for 1997”. dga.org. Directors Guild of America. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- “Outstanding Directing For A Miniseries Movie Or A Dramatic Special Nominees / Winners 1998”. Television Academy. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “Sci-fi acad sends pix into orbit with Saturns”. June 15, 1999.

- “The Movie Masterpiece Award”. empireonline.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “CONFUSING LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT WITH STAR POWER”. Sun Sentinel. February 9, 2000. Retrieved August 13,2023.

Ms. Burke handed over the dais to producer Richard Zanuck (Jaws, Driving Miss Daisy), who would present the evening’s first Lifetime Achievement Award to director William Friedkin.

- “Festival Awards”. fipresci.org. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “CineMerit Award”. www.filmfest-muenchen.de. Filmfest München. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- Mayorga, Emilio (May 31, 2017). “William Friedkin to Be Honored at Spain’s Sitges Festival”. Variety. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- “The Festival – Special awards – Pardo d’onore Manor”. Locarno Film Festival. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- “Venice Film Festival: ‘Faust’ wins Golden Lion award”. Los Angeles Times. September 10, 2011.

- Aftab, Kaleem (June 7, 2012). “Killer instincts”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

Was in competition at Venice, where it won the Golden Mouse (online critics’ best film).

- “‘Beasts of the Southern Wild’ reçoit le Grand Prix de l’Union de la Critique de Cinéma”. RTBF.be (in French). January 6, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

Cinq films étaient en lice pour cette récompense: “Beasts of the Southern Wild”, de Benh Zeitlin, “Take Shelter”, de Jeff Nichols, “Shame”, de Steve McQueen, “Ernest et Célestine”, de Benjamin Renner, Vincent Patar et Stéphane Aubier, et “Killer Joe”, de William Friedkin.

- Busis, Hillary (February 20, 2013). “Saturn Award nominations announced”. EW.com. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- Truitt, Brian (February 20, 2013). “‘The Hobbit’ leads Saturn Awards with nine nominations”. USA Today. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- Cohen, David S. (June 27, 2013). “Saturn Awards Honor William Friedkin”. variety.com. Variety. Retrieved August 12,2023.

- Turan, Kenneth (August 27, 2013). “William Friedkin celebrates a Golden Lion, restored ‘Sorcerer'”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 12, 2023.